To Convene, to Confer: On Attending the 2015 AWP Conference in Minneapolis

By Katie Naughton

“How was AWP?” a friend asked when I returned from Minneapolis.

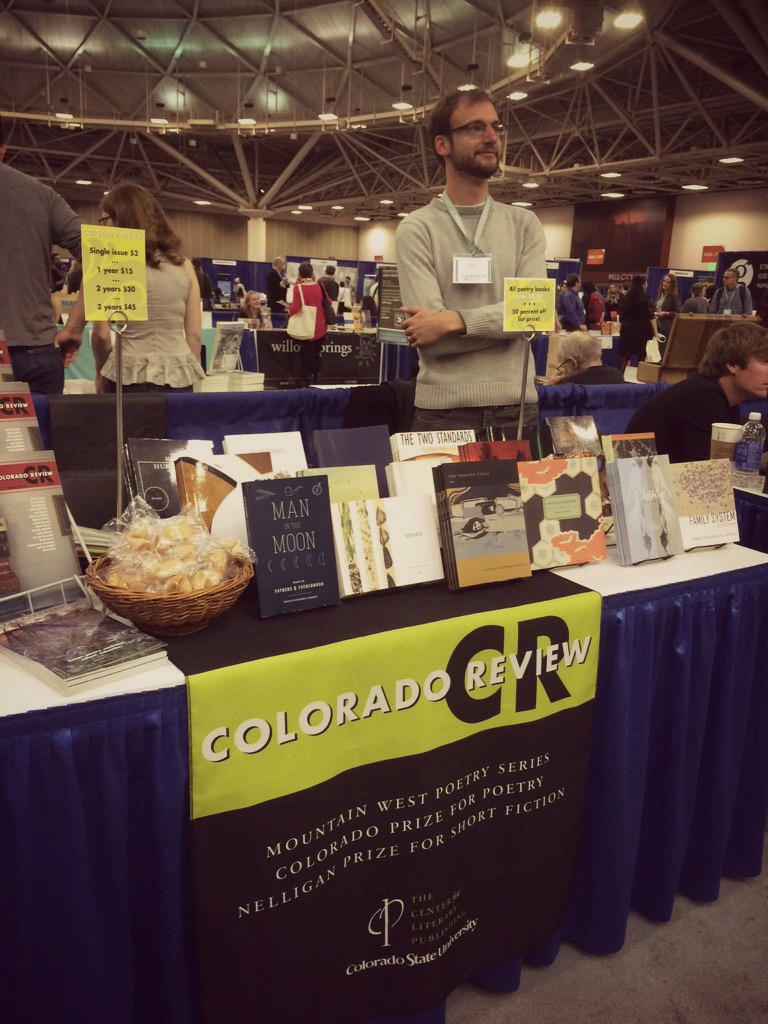

I had just spent four days at creative writing’s largest academic conference, hosted by the Association of Writers and Writing Programs in a different city each spring. It assembles more than 12,000 attendees; 2,000 presenters; and 700 presses, journals, and literary organizations to come together for about 550 readings, panels, and lectures, and for one very, very big book fair. Generous funding from the Department of English, the Dean of Liberal Arts, the Office of the Vice President for Research, and the Center for Literary Publishing (Colorado State’s own literary press) made it possible for me and eleven other CLP graduate student interns to be among those 12,000, attending panels and readings and running the CLP’s table at the book fair[1].

After waking up at seven the first rainy morning of the conference for a shift volunteering at registration (I handed out probably thousands of pounds of conference schedules stuffed into hundreds of AWP’s iconic tote bags), I entered into the immersive three-day experience at the Minneapolis Convention Center (connected to one’s hotel by a labyrinth of second-story corridors known as a skyway) and attended a panel at which Cal Bedient, Cole Swensen, and Eleni Sikelianos gave a brilliant overview of the history of the lyric and the experimental poem and its capabilities, its ethical responsibilities. At another panel, Dawn Lundy Martin, Sarah Fox, and Joseph Lace thought about the links between activism and poetry in a discussion that shared many surprising overlaps with the panel on the experimental lyric. I heard some long-time favorites Anne Carson and Forrest Gander read for the first time, and in the process was completely blindsided by the work of some poets I hadn’t known before: Claudia Rankine, Fred Moten, and T. C. Tolbert.

I was also able to introduce myself to an editor whose journal I admire, who encouraged me to submit some of my own work, and to meet the editor who had just chosen a friend’s story for publication and for a small fellowship. At the book fair, I bought the first book of an old friend I used to sit with in a Brooklyn loft among a group of very young poets drinking whiskey and talking through poems. I met up with former classmates who have gradated from CSU and moved on to new cities and new studies; I accidentally ran into the poet who taught me as an undergraduate and was able to remind her of a poem I had written as homework in a literature class as an eighteen-year-old, on which she had made a quick note of encouragement—“you should probably keep writing poems”—the first such note I had ever received.

Despite or perhaps because of all this, though, in my post-conference exhaustion the best answer I could give to my friend’s question about the conference was “I think I’m doing better this year than last year.” What I meant was that it feels like AWP is, as much as anything, a kind of test, the externalization and magnification of an inner proving ground. I had the sense that, between years one and two of my MFA program, I had learned some things about poetry—where my interests lie and who I want to be as a writer—that made the conference less unnerving than it had been the previous year.

Numbers aren’t necessarily our strength as writers, but it seems evident that 12,000 is a lot of writers and 550 is a lot of events to fit into a period of about 72 hours. I thought maybe as a way to wrap my head around these numbers, to get a sense of what we do when we spend time in this kind of assembly, and to understand what I mean by AWP being a kind of test, I might think about some words, specifically convention and conference, convene and confer, because when I don’t quite know what I mean, I often find it helpful to ask the words what meanings they carry with them.

Both from the Latin, says the Oxford English Dictionary, con-, “together,” ferre, to bring, to bear; venir, as in “to come.” Conferre, from which we get confer and conference, “to bring together, to collect, gather, contribute, connect, join, consult together, bring together for joint examination, compare.” Convenire, from which we get convene and convention, “to come together, assemble, unite, agree, suit, fit, befit.” Together, we come, we bring, we bear.

With convene and convention come “a common purpose,” “a collective body,” “united action,” “to harmonize, to fit together.” And “important matters, ecclesiastical, political, or social,” “accepted usage, standard of behavior, method of artistic treatment,” “accepted usage become artificial and formal,” “the action of summoning before a judge.”

Conference and confer bear with them “to converse […] now always on an important subject or some stated question,” “to take counsel,” “a formal meeting.” And also “‘witches, that pretended conference with the dead,[2]’” “to put the sense together, construe,” and “to give, grant, bestow, as a grace, or the act of a qualified superior.”

We come, we bring, we bear, together. These words reach after a sense of the positive aspect community: the act of occupying a common purpose, a collective body, a united action; the act of contributing something tangible, as a grace, when we arrive; the act of putting the sense together as something bigger and truer than it could be as separate senses existing individually.

The words aren’t simply positive, though. It is as if they contain a Janus face, this positive aspect pressed right up against, inseparably, a negative aspect: a hidden and inherent sense of hierarchy, a judge that may summon us, a qualified superior whose grace we must court, an unnamed authority laying claim to what can be called acceptable and important. This authority requires that we consider the right questions, engage in this act of community with some respectable formality, with the possibility of violence in fit if the pieces aren’t cut to harmonize.

Perhaps it is this Janus face that makes community something of a site of anxiety for me. It seems there is the possibility both of beneficent influence and of destruction. It seems that community has to be approached with some care.

This might be partially because, on one hand, the act of writing, of writing lyric poetry perhaps especially, seems to require an almost obsessive attention to a private logic— that which I know about the world because when I shut out the voices of conventional explanations and listen as truly as possible, it is what I hear.

But on the other hand, poetry also hopes to extend past the limitations of the private self, the lyric I. It hopes both to reach readers who might hear in the poem something like what the poet him or herself hears, and to engage in a poetic work that extends beyond the concerns of the self in isolation, that addresses a lyric you, that does the work of building community, that does the work the community needs it to do.

In my experience, it is always difficult to strike a balance between reaching in and reaching out, of opening up the private logic to the consideration of matters beyond the self, but of staying true to what that self is truly hearing. A convention like AWP challenges that balance by adding to it the pressure of presence of the community. This pressure is benevolent—it asks our poems to stand up to the responsibility of engaging beyond our own experience, it listens to what we hear, it speaks to us what it knows, it magnifies our actions by unifying them with its own. This pressure is destructive—it stands as an authority and judge, asks us to listen not for what we know but for praise, to work not for the poem but for recognition.

What is the test, then, of convening, of the conference? To come from your solitary work, your small communities in your small cities or towns, and to bring with you . . . what? To bring with you your sense, your grace. To allow yourself to be summoned before the judge, the community, its two faces exhilarating and horrifying. To ask to hear one poem and to hear instead another. To look for one community and to find instead another. To hear a voice that does not fit and not to do violence to it. To, in your exhaustion sometime around hour 56, shed, if just for a moment, whatever BS you’ve been carrying around about being accepted or acceptable, to look at yourself and try to remember what must remain important to you, to consider what in you has become artificial and formal. To decide that, for a poem, the formal must also conference with the dead, as a witch, as important ecclesiastical matters, as grace. To acknowledge the spiritual, metaphysical, ethical obligations and complications of we, together.

How do you pass? Take notes. Take counsel. Learn something. Take home the books of Claudia Rankine and Fred Moten and learn what they are teaching you about the lyric you, community that you see and community that you don’t, and the responsibility to see harder. Do your work. Bear the responsibility of community back with you to your desk, to your solitary work, your small community, your small town. Keep writing. You don’t matter. You do.

[1] If you’re curious about what this was like, be sure to check out all our social media posts from the weekend by following the CLP on Twitter (@Colorado_Review) and Facebook (facebook.com/coloradoreview).

[2] T. Hobbes, Leviathan i.. xii. 56 (1651)

Katie Naughton is a second-year student in CSU’s Creative Writing MFA program, where she is studying poetry, teaching composition, and working as an associate editor at Colorado Review/Center for Literary Publishing. Prior to arriving at CSU, she lived in New York and in Thailand, where she taught English as a Fulbright grantee. She holds a BA in creative writing from Hamilton College and grew up in Cromwell, Connecticut. Her poetry can be found online in Lambda Literary’s Poetry Spotlight and in Underwater New York.