~from Jill Salahub

Indian writers might come from different eras, from different geographies, from different tribes, but we all have one thing in common: We are storytellers from a long way back. And we will be heard for generations to come. ~James Welch

As an undergraduate at Oregon State University, I took a Native American Literature class taught by Linc Kesler, who is of indigenous ancestry himself, (Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge South Dakota). In that course, we read two novels by James Welch — Fools Crow and The Death of Jim Loney. Even though I’ve long ago donated various Norton Anthologies and Shakespeare plays and a collection of other novels from those days, I still have my copies of James Welch’s books, along with all the others we read in that course. They are worn, with pages of underlined text and notes written in the margins. With close to twenty years of time passed, I can’t remember the exact discussions we had in class or what I may have said about them in papers I wrote for the course, but I do remember how those stories haunted me. Fools Crow and Jim Loney were characters both heartbreaking and epic, beauty and brutality that stays with a reader for years after.

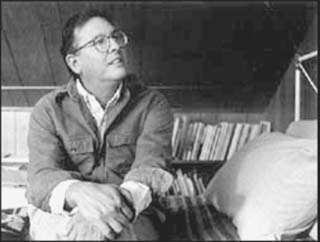

According to a piece published in The New York Times upon his death in 2003, James Welch “grew up on an Indian reservation, determined to become a writer and put into words the stresses on a people left out of the American dream.” While best known for his novels, Welch was also a poet, and considered a founding author of the Native American Renaissance. In an interview from 2001, Welch said, “Although I consider myself a storyteller first and foremost, I hope my books will help educate people who don’t understand how or why Indian people often feel lost in America.”

James Welch was born in Browning, Montana on November 18, 1940. His father was a member of the Blackfeet tribe and his mother of the Gros Ventre (A’aninin) tribe. After high school and before beginning his study of English Literature at University of Montana, Welch worked as a firefighter for the U.S Forest Service, as a laborer and as an Upward Bound counselor. Once he finished school, he went on to teach and write. In addition to his literary work, Welch served as the Vice Chairman of the Montana Board of Pardons and Parole for ten years. He has honorary doctorates from the University of Montana, Montana State University and the private Rocky Mountain College in Billings.

James Welch wrote poetry exclusively for 7 or 8 years before writing fiction, even though he’s best remembered for his novels. When at University of Montana, he studied with poet Richard Hugo, who told him that “his poetry needed roots, so he should write what he knew about. Write about Indians and Indian culture. Write about home.” Even though at the time he was skeptical that anyone would want to read about the Indian experience — “I knew that nobody wanted to read about Indians, reservations, or those rolling endless plains that turned into Canada just thirty miles north” — he took the advice and began to publish and find his audience. “Happily, I was wrong in thinking that nobody would want to read books written by American Indians about American Indians and their reservations and landscapes.”

Along with writing and teaching, Welch also worked with Paul Stekler on “Last Stand at Little Bighorn,” an Emmy award winning documentary which aired on PBS. Together they also wrote the history, Killing Custer: The Battle of Little Bighorn and the Fate of the Plains Indians. Welch’s first novel, Winter in the Blood, was adapted as a 2012 feature film by the same name with Native American writer Sherman Alexie helping to produce the film. Welch’s work earned him many awards and accolades, including a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas.

James Welch died in 2003 in in Missoula, Montana. He suffered a heart attack after battling lung cancer for ten months. Upon his passing, poet Richard Hugo’s widow said, “He was a lovely man, a warm friend. He was great fun in the gentlest kind of way. His writing style was beautiful imagery. It has the poet in it, a quiet mastery of characterization. He was a great man and a great writer.”