David Shields is a controversial figure in the creative nonfiction world: someone who pushes the boundaries of genre and sometimes inspires strong reactions in his readers.

In his introduction to Shields’ reading at the Lory Student Center, first-year M.A. student Caleb Gonzalez emphasized how Shields challenges the conventions of literary nonfiction. After reading Reality Hunger in Harrison Candelaria Fletcher’s nonfiction workshop, Gonzalez said, “I am now summoned – as David Shields frequently summons his readers to do – to question what I write, how I write it, and why I write it. He invited me to question what fiction and nonfiction really is. He invited me to think about the idea that if the genres of literature are never to be questioned and challenged, they could not stand the test of time.”

Shields is the author of over twenty publications. Reality Hunger, a collage manifesto, explores the possibilities of creative nonfiction and the notion of “truth” while challenging and questioning some of the criticisms and limitations often placed on nonfiction as a genre. Over thirty publications named Reality Hunger as among the best books of 2010. Shields’ other critically-acclaimed publications include New York Times bestseller The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead and a National Critics Circle Award finalist, Black Planet. In February of this year, Shields published his most recent work, Other People: Takes and Mistakes.

At CSU the day before, Shields had showed his film I Think You’re Totally Wrong: A Quarrel. The film, directed by James Franco and released this year, is based on a book of the same name published by Shields and his former student Caleb Powell in 2015.

Like Reality Hunger, I Think You’re Totally Wrong is meta-art. Shields and Powell hold contrasting views about the role an artist’s life should play in his or her art. Does an artist have an obligation to expose his or her own weaknesses and shortcomings through art? Is an artist obliged to protect other people in his or her life or to obtain permission before writing about others? These difficult questions come to a head in I Think You’re Totally Wrong in raw and uncomfortable ways, as the artists break the fourth wall and debate about what to share and what to keep private in the film itself.

At his reading, Shields read a number of essays from the recently published Other People: Takes and Mistakes. These included an essay about former president George W. Bush. Shields opposed many of Bush’s policies, yet the essay empathetically emphasizes those character traits with which the author himself identifies. He also read essays about a cruel joke his middle school classmates played on one another, an uncomfortable encounter with OJ Simpson in a Häagen-Dazs ice cream store, and a thoughtful response to Shields’ own most critical reviews.

After the reading, Shields answered a number of questions from the audience. MFA student Meghan Pipe wondered whether Shields ever feels the need to revise a piece after it is published, especially given that creative nonfiction often comments on events or topics that continue to develop, such as Shields’ essay about OJ Simpson, which describes events which took place before Simpson’s famous trial. Shields agreed that it’s very tempting to continue tinkering with a piece after it’s published, but he has never re-written a previously published work.

MFA student Yash Seyedbagheri asked a challenging question about Reality Hunger and its exploration of truth. Given the recent concern about “fake news,” as well as accusations made against the Trump administration of falsifying information, Yash Seyedbagheri asked whether Shields still stands by what he wrote in 2010 about the difficulty of determining what is “true.”

Shields conceded that he has also thought about this question and wonders whether his approach to creative nonfiction could be used to validate fake news. Shields nonetheless defended his assertion that nonfiction should question what is true in a thoughtful and intentional way. “What we’re doing in our form is trying to investigate truth and acknowledge our deep flawedness, and that seems very different from what Donald Trump seems to be doing.”

Caleb Gonzalez had ended his introduction to the reading with a prediction of what the reading had in store: “Without a doubt,” he said, “what David Shields has to say will be interesting, stimulating, absorbing, gripping, and let us not forget challenging.” Gonzalez’s prediction was certainly true for me; I left the reading still wrestling with the difficult questions Shields’ work posed.

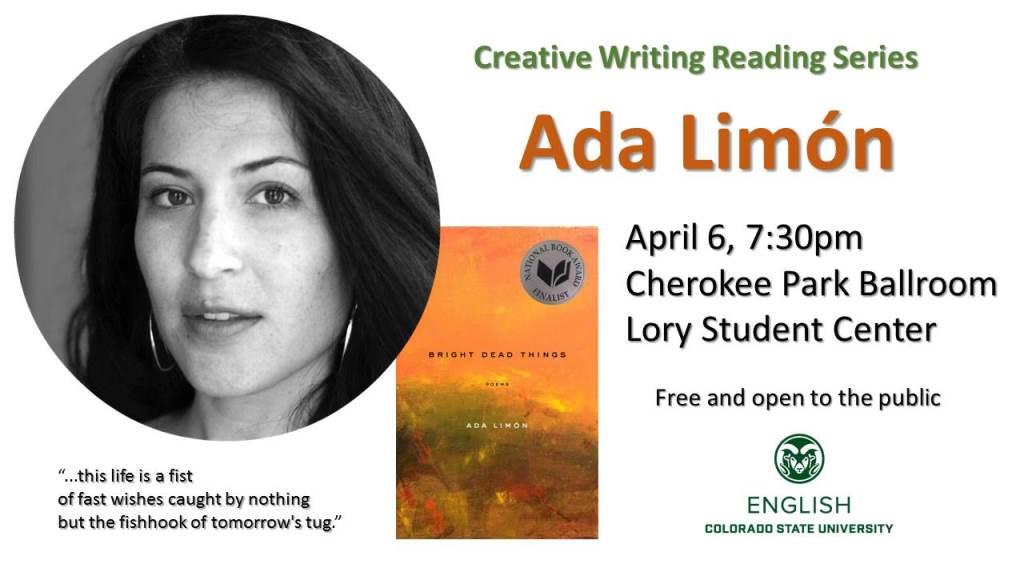

There are two more readings in the Creative Writing Series this semester. We’d love to see you there.