~from communications intern Joyce Bohling

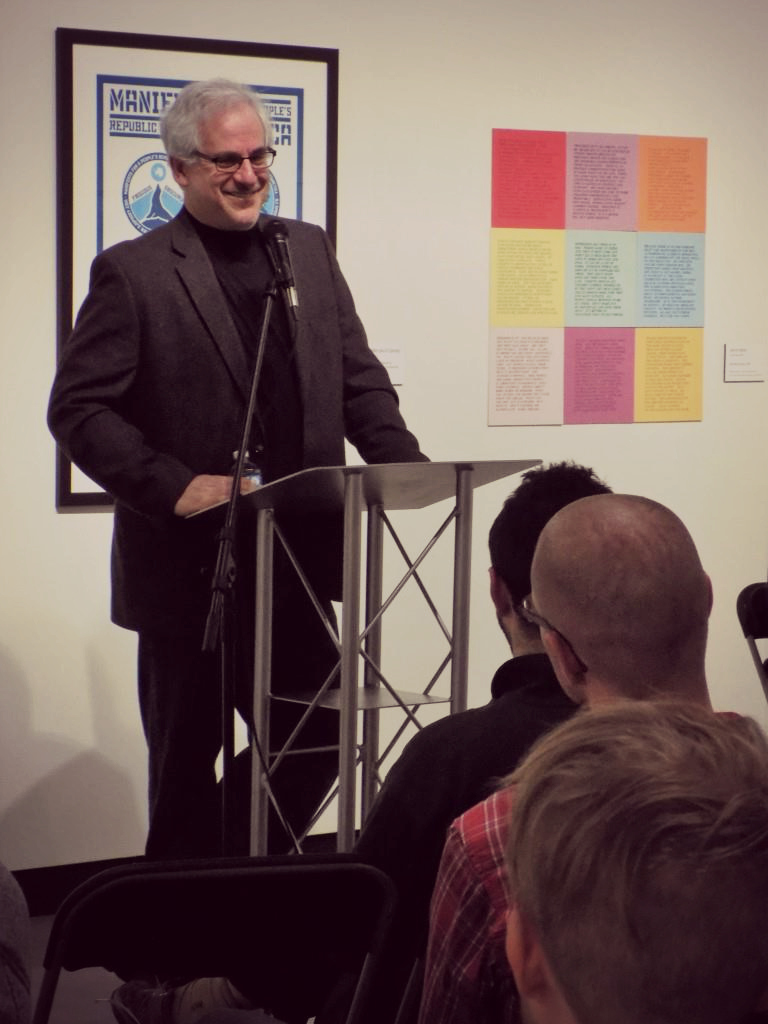

The Creative Writing Reading Series is a special opportunity for CSU students to hear established and esteemed authors from around the nation present their work, and when fiction writer Ethan Canin came to campus on Thursday, January 26, students were given an additional chance we don’t often get: to ask questions directly of the author and solicit his advice.

Canin is the author of seven novels, including, most recently, The Doubter’s Almanac. As fiction M.F.A. student Yash Seyedbagheri said in his introduction: “Mr. Canin lets his characters trip themselves up.”

Canin himself would agree with this assessment. Fiction, he says, is fundamentally about people misbehaving; he actually described novels, in his talk, as “compendiums of misbehavior.”

At the question and answer session in the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art on Thursday evening, whose audience mostly consisted of graduate students in the creative writing and creative nonfiction programs, as well as some faculty and undergraduate students, topics of discussion ranged from techniques for outlining and mapping a novel, the role of electronic communication in fiction, and the existence of objective truth.

Myself a graduate in creative nonfiction, I found some of the advice familiar. Write every day, for instance, is a tried-and-true mantra of the writing profession that Canin re-iterated, describing how writers he knows went so far as to purchase or rent their own office spaces so that they could commute in to “work” like nurses or engineers or lawyers and spend the day on their craft, free from distractions.

He told his mostly student audience that they should be learning two things: “how to write,” and “how to be a writer.” By the latter, he meant that students should establish the habits that will make them successful writers, like writing every day.

But Canin also described aspects of his writing life that are unique. Before becoming a full-time writer, for instance, he worked as a doctor. He even joked that when his short stories were published in literary journals, his colleagues in the medical profession sometimes commented that they liked his “articles.”

Canin was also honest about the hardships of being a writer: the difficulty, he seemed to be saying, in placing the success of one’s career on a piece of art. Writing is “the hardest freakin’ thing in the word,” he said: more difficult, even, than being a doctor. He has “not written one [novel] when [he] wasn’t distraught” about whether the work would be successful.

Yet Canin believes writing is worth the challenge because of the way it creates empathy for other humans, something which, he said, is especially important in a time of such political polarization.

One of the “only” pleasures of writing, he said, is “the moment when you become somebody else.”

And indeed, Canin has deep empathy for his characters, even though they are flawed and so often “trip themselves up.”

Of his characters: “I feel like I am every single one of them.”

Though it may seem to strike a dark note, to talk about just how difficult writing is to an audience of people who have committed to or are in the process of committing to the writing life, I found it weirdly encouraging. If grad school has taught me one thing, it’s that writing is a messy, long, sometimes painful, sometimes even embarrassing process. More often than not, I am, to use Canin’s word, “distraught.” And so to hear a writer tell us that he still feels this way, seven published books down the line, makes me weirdly sort of hopeful. Maybe distress is something normal, even healthy, to the creation process.

And I agree with Canin that this distress does have its payoff. In a time when our country’s emotions are running high, when we are quick to point fingers, to accuse, or to explain away the things really troubling us, creating thoughtful literature that builds empathy and wrestles with difficult questions is an especially important pursuit, whatever challenges we face doing so.