Read this story in the 2019-2020 CSU College of Liberal Arts Magazine, titled Lenses of the Liberal Arts: Space and Place.

Updates since publication

May 2020 — Abigail Chabitnoy wins the 2020 Colorado Book Award in Poetry for How to Dress A Fish.

April 2020 — How to Dress A Fish is shortlisted for the Griffin Prize.

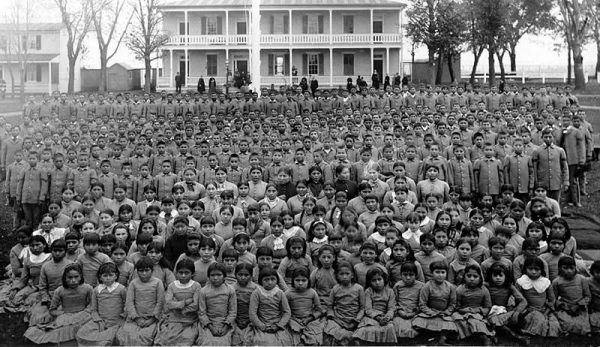

In 1901, Abigail Chabitnoy’s great grandfather, Michael, was sent from his native Kodiak, Alaska to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the first federally funded boarding school established to affect rapid assimilation of Native American people into Euro-American culture by separating children from native influences, especially family.

About a century later, Abigail grew up about an hour away from the school, unaware of its historical legacy and what that has signified for her family and heritage.

“I knew from an early age about our name and vaguely about it being Russian, and about why it was Russian but we weren’t Russian,” Chabitnoy said. “We really only had that little bit of our history, and we knew my great grandfather went to Carlisle.

“In Pennsylvania, at least where we went to school, we didn’t really learn about Carlisle. And if we did, it was just a footnote. There wasn’t any detail to what happened at the school.”

Cultural suppression of Alaska Native people followed the 1867 U.S. purchase of Alaska from Russia, which had controlled the region since the late 1700s. Russians had largely integrated among indigenous people and had allowed native traditions to persist for the most part, hence the Chabitnoy surname.

Methods used at the school included banning native languages and traditions, as well as corporal punishment for enforcement. The school’s practices and its effects on descendants of native people, like Chabitnoy, remain controversial.

Curiosity about her origins built up for Chabitnoy around 2005 as she prepared to enter undergraduate studies in Pennsylvania. That’s when her father informed her about scholarship opportunities available through the “corporation” to which she belonged.

“It was weird, ‘I don’t belong to a tribe; I belong to this corporation,’” she said.

Member of a corporation

Chabitnoy’s father was a graduate student in Washington D.C. in 1971 when the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was signed into law. He found public library records of Michael Chabitnoy’s time at the Carlisle School, and the records proved his own Aleut bloodline. They also marked his family’s eligibility for benefits under the new law.

The 1971 act paid land and money to Native Alaskan people to settle growing land claims after the 1968 discovery of Alaska’s largest oil field in Prudhoe Bay. To manage distribution of the money and land, the new law separated Alaskan indigenous people geographically into 12 for-profit corporations. Alaskan Native people born before the act were made shareholders, and descendants like Abigail Chabitnoy are members.

Her family belongs to the Koniag Corporation, which encompasses Kodiak Island and her native Tangirnak Native Village. She learned about her corporation as a source of scholarship money while applying for university.

“There was this group within the corporation whose mission was to fund education for students of Alutiiq descent,” she said.

The essay she wrote for the Koniag Education Foundation addressed how her studies would contribute to the Aleut people, culture, and village.

“Of course, being 18, knowing very little about being Alutiiq, I said something like, ‘I’ll study anthropology and of course that will be helpful and bring attention…in that direction,’” she said.

The essay garnered a scholarship, and by the time she finished undergraduate coursework in anthropology, she had also completed an internship in Anchorage, maturing her understanding of Aleut culture through still-limited interactions.

“I got to read transcripts from tribal elders where I could see them talking about the culture,” she said. “…But I was still removed from Kodiak, and the landscape of Kodiak is very different from Anchorage.”

By the time she entered graduate studies in the English department at Colorado State University, Chabitnoy had become immersed in folklore and myth.

“It’s one of the things that attracted me to anthropology in my undergrad, these different ways of telling stories and viewing the world,” she said.

When she began the thesis project that became How to Dress a Fish, her master’s thesis and debut poetry collection, she had developed an interest in certain Navajo figures as prospective influences on her writing. But her perception of these influences as myth and folklore did not match their sacred regard within the Navajo culture.

“It’s not just some literary trope or a bedtime story,” she said. “It’s a very significant cultural aspect that I can’t fully understand.”

In that realization, she found a parallel between her limited understanding of the Navajo and the Aleut.

“That was my ‘ah-ha’ moment,” she said. “If I was going to look at stories to interpret my world, I needed to look at stories from this culture, which has been supporting my education and calling me back for all these years.”

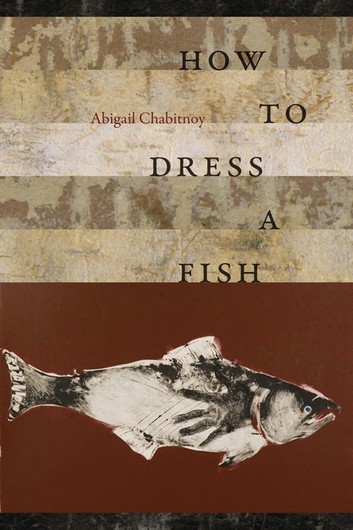

In the poetry collection, Chabitnoy explores her journey to connect with her roots among the Alaska Native Aleut through letters, Michael’s school records, and historical photos.

“This work seeks to redefine history through family, Aleut culture and story to address questions of the relationship of culture, place, and the individual,” Chabitnoy writes in the thesis abstract.

As her focus shifted toward developing a project around her own roots, Kodiak was experiencing cultural revitalization.

“They were really diving into relearning their language and teaching it to their youth. They were bringing back traditional dance that hadn’t happened since before the U.S. took control,” she said.

Trip to Kodiak

Ironically, it was after writing How to Dress a Fish that Chabitnoy first visited Kodiak, for 10 days in 2018.

“I was terrified to go because I thought this illusion would be shattered,” she said. “This idealistic vision I had of what it would be like to go there wouldn’t live up to my idea of it, and it would just be devastating.”

And, as expected, Kodiak proved somewhat anti-climactic, she recounted, comparing it to most modern rural U.S. towns. But on the same trip, she took a boat to neighboring Woody Island where Michael had lived.

“Stepping onto Woody Island, the difference was immediate,” she said. “I knew that Michael had been there. I knew he’d lived there for a time, and I could feel it. It was the visceral embodied knowledge that I was sharing space with my ancestors. You can see Kodiak from Woody Island, but you’re still removed from it. It was like lifting a veil to reveal this different place.”

Meanwhile, engaging with her native contemporaries for a brief time in Kodiak yielded conflicting emotions. It put certain anxieties to rest while accentuating gaps in Chabitnoy’s understanding of her culture and history.

“Everyone there who I met could really relate to the journey I was on, and to that longing for knowledge, and they were open to it,” she said. “But also I was there for 10 days. I wasn’t embedded; I wasn’t dancing with the group; and I still felt that sense of being an outsider.”

She admits that a certain level of integration with her people can never exist due to physical distance, and due to deliberate cultural divides like the Carlisle School.

“When I talk to other Native writers, there seems to be an immediate recognition of ‘well, yeah, that is the heritage of the boarding school, and that is exactly what it was designed to do, and I have every claim to write that story,’” she said.

“But there were times when I was writing the book that I stopped and questioned myself, ‘how much of this heritage is still mine, and how much ownership do I still have to write these stories?’”

A mentor within the English department at CSU, poet and professor Camille T. Dungy, encouraged her to persist.

“’If you don’t write this book, and if you don’t keep following this research, basically you’re giving into the legacy of Carlisle and the history ends with you,’” Chabitnoy recounted. “So as much as was ruptured, and as much as can’t be recovered, it still became imperative to recover what I could.”

Still, Chabitnoy sets limits to her cultural license.

“With my book, I very much wanted to focus on my story and my family’s story, as opposed to the overall Alutiiq story,” she said.

In her thesis abstract, Chabitnoy writes about incorporating Michael’s student records, language from early ethnologies, Unangan storytelling, and Alutiiq tradition.

“It engages documentary poetics to give witness not only to the treatment this people has already endured, but also… to give testimony to a people that persists today…,” she writes. “…This work is personally significant as a gesture of gratitude and act of reuniting with my ancestral culture.”

Now and the future

After graduating from her MFA program, Chabitnoy worked as a freelance writer and took a job in retail while continuing to focus on her craft. She admits it was difficult to begin writing again after completing her thesis.

“It’s almost like there was too much closure (in finishing the book),” she said, pointing out that she still had a collection of unreviewed research materials.

“I didn’t know how to move forward without feeling like I was just continuing to rewrite that same book over and over again.”

In 2017 she began working full-time with a consulting firm that supports indigenous self-determination. Today, she works there part-time while maintaining sharp focus on her writing, exploring issues of cultural identity in storytelling. So that she can continue immersing herself in poetry and the humanities, Chabitnoy is considering a Ph.D. program.

About Abigail Chabitnoy