When we think of the Vietnam War era on college campuses, doubtless antiwar protests come to mind. Although the antiwar movement’s presence was certainly felt at CSU in the 1960s, Fort Collins was not Berkeley or Madison. In fact, James Hansen reports in Democracy’s College in the Centennial State that CSU students were “a highly moderate, and even conservative” group, according to surveys of attitudes on campus. In October 1965, for example, the student legislature passed a resolution supporting President Lyndon Johnson and the war:

Its primary purpose is to support your present policy stand in Vietnam. And its secondary purpose is to indicate to the leaders of our nation that we, the American students, wish to take as active a part in such vital national and international affairs as is is feasible in our position.

In Jan. 1968, a student referendum about the war revealed that 82% opposed withdrawal of troops from southeast Asia, and 51% supported increased military action there. Later that year, students would voice support of “CSU involvement in war related research projects.”

The State Board of Agriculture, CSU’s governing body, showed strong support of the war as well when they voted in 1966 to not allow military service deferments for employees with National Guard or Reserve assignments who were called up for duty.

In spite of this dominant stance, resistance did exist. First signs may be found in students’ successful push to eliminate mandatory participation for men in ROTC that had originally been a requirement of the Morrill Act. Hansen writes that although early antiwar efforts were unfocused, that changed by 1967 when “a group of local citizens, faculty, and students formed to consider ways of protesting the war. These individuals all tended to be respectable and moderate, and came to regard politics as the key to effecting desired change….Also notable at this time was the activity of the Students for a Democratic Society, a politically radical group that initially concentrated on opposing the selective service law, but became increasingly committed to anti-Vietnam activity.”

Antiwar activities included student protests at speech by US Army General Maxwell Taylor at the Student Center in November 1967, a Peace Ball held as an alternative to the Military Ball in April 1968, and a February 1969 performance by antiwar activists and folksingers Joan Baez and her husband David Harris.

A major protest event had ties to the English department. Poet Galway Kinnell was a visiting writer in residence “who lent some important coordination to disparate individuals who objected to the war but as yet lacked a clear idea of how to implement their views,” according to Hansen. In 1968, Kinnell led a group called Peace Action Now in a march to the war memorial in downtown Fort Collins. On March 5, several hundred people—mostly faculty and students—joined an antiwar protest that drew much counter protesting, some of which was quite violent.

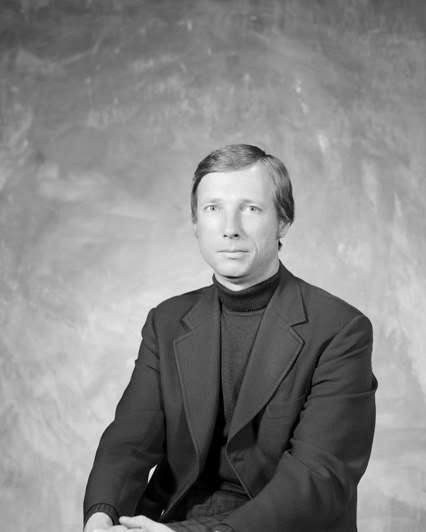

Meanwhile, two writers who would later come to the English department were serving in Vietnam. John Clark Pratt, an Air Force officer who was an English instructor at the Academy in Colorado Springs, spent a year on what he called his “Vietnam sabbatical” in an interview for the Senior Scholars Oral History project. He was assigned as a writer for the Contemporary Historical Evaluation of Combat Operations (CHECO) which “wrote top secret documents for the Pentagon on various events, and various aspects of the war…[in] Thailand [at] Odorn Air Force Base, [serving] as commander of the Thai Project CHECO outfit.” Because he wanted to maintain his pilot skills, he assigned himself to flying missions while there, resulting in “over a hundred combat hours in eight different kinds of aircraft.”

Clark retired from the Air Force as a Lieutenant Colonel and was hired as CSU English department chair in 1975. He remained on the faculty until his retirement in 2001, teaching creative writing and literature courses. “His Vietnam experience provided the foundation for subsequent landmark publications including The Laotian Fragments (1974), and Vietnam Voices: Perspectives on the War Years 1941-1982 (1983), which was called ‘the “absolute best” book on the Vietnam War’ and ‘perhaps the best one-volume introduction to the literature of the war,’ according to his CSU obituary. He was also instrumental in developing the Vietnam War Literature Collection at Morgan Library, among his many accomplishments during his tenure at CSU.

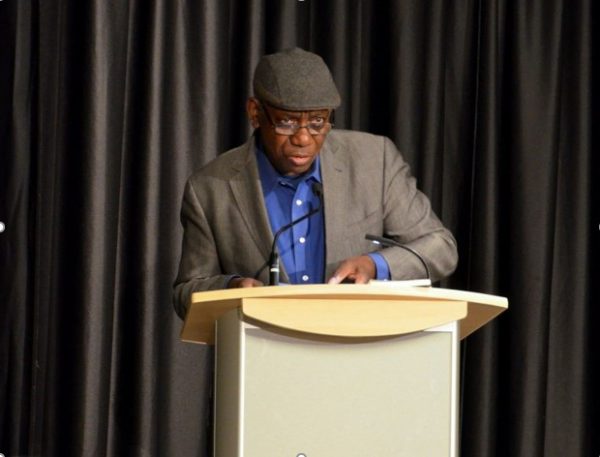

Another Vietnam veteran arrived at the CSU English department in the 1970s as an MA student. Yusef Komunyakaa served one tour in South Vietnam in the mid-1960s as the managing editor of a military newspaper. He received a Bronze Star for his service. Komunyakaa earned an MA in English at CSU in 1978 and went on to publish numerous books of poetry. His many writing awards include the Pulitzer Prize, Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, William Faulkner Prize and Wallace Stevens Award. Currently, he occupies the Distinguished Senior Poet chair at New York University. His work has mined his Vietnam experience, among other subjects, and on Friday of a week that began with Veterans’ Day, it seems fitting to end with an excerpt from his poem “Facing It,” a meditation on a visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way—the stone lets me go.

I turn that way—I’m inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.