In spite of CSU President William Morgan’s strong belief in the value of humanistic education and of the renaming of the institution as a university, expanding the school’s emphasis beyond vocational training did not happen immediately.

The research function of the university was well underway, increasingly paid for by public and private grants and contracts. The Colorado Agricultural Research Foundation, founded 1941, exerted significant influence on the campus throughout the 1950s. According to James E. Hansen’s Democracy’s College in the Centennial State, the Foundation, along with a land-use charge on bonds issued to fund housing construction, “the school accrued vast holdings of incalculable value at virtually no cost to the state of Colorado.”

As several dormitories and classroom buildings rose on campus in Fifities, so did the Foundation’s role in “the administration of grants, the encouragement of inter-disciplinary and inter-departmental projects, the stimulation of research throughout all sectors of the institution, and the development of contacts with public and private granting agencies.” Research funding flowed into CSU’s coffers, but tended to pool in areas of science and technology directly connected to fighting the Cold War. Agencies such as the Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, and National Institutes of Health wrote big checks for the study of the effects of radiation or threats to the food supply.

Funds for scholarship in the social sciences and humanities, however, were scarce. While CSU urged departments in these areas to pursue grants from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare or the National Endowment for the Humanities, these disciplines remained dependent on largely on state funding and their mandate to serve the rest of the university. Professors were paid less, taught more, and found little support for conducting the work that would generate new knowledge or creativity in their fields.

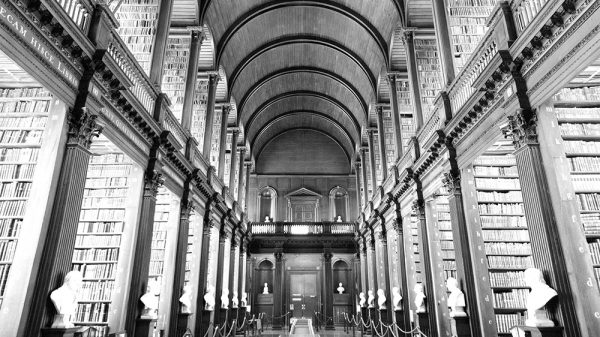

A 1959 visit from the North Central Association found CSU lacking in the qualities of a true university, such as broad-based education for students, an adequate library, and faculty equity. Among the concerns was “the professional colleges’ [continuing] to ignore any substantive commitment to the ideal of a general education.” Their report stated, in part:

At a time of concern for fragmentation of knowledge, and when most professional programs seem to be moving towards a strong liberal arts or general education orientation, much might be done at Colorado State University to insure that the graduate is a broadly educated individual, and not possessed of a narrow experience more comparable to a strict trades apprenticeship.

Hansen attributes resistance to curricular change toward liberal education to self-interest among members of the Faculty Council Executive Committee, reluctant Deans, and a skeptical Colorado legislature. He reports that the next North Central visit found even more evidence of neglected humanities and social sciences.

English composition was one of few university-wide requirements for undergraduates in this era, as it had long been. But the department was not limited to service in the late 50s. Its Master’s of Arts program was underway, there were over 100 majors, and faculty were productive. In 1958, for example, Roy C. Nelson and Lester H. Stimmel were promoted to full professor and Edgeley W. Todd and Randall Ruechelle gained tenure and promotion to associate professor.