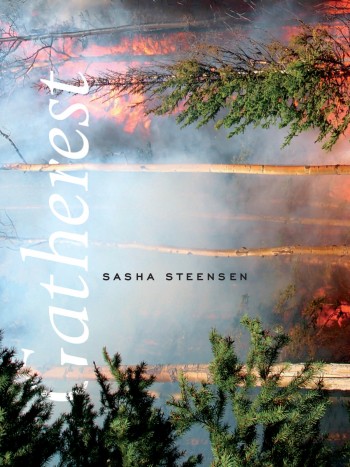

As we continue highlighting our “local” poets (faculty and alumni), today we feature Associate Professor Sasha Steensen, and in particular her latest book of poetry, Gatherest.

Sasha Steensen is the author of four books of poems: House of Deer, The Method, and A Magic Book, all from Fence Books, and most recently, Gatherest from Ahsahta Press. Recent work has appeared in Kenyon Review, West Branch, Omniverse, and Dusie. “Openings: Into Our Vertical Cosmos” was published as an online chapbook by Essay Press. She teaches Creative Writing and Literature at Colorado State University, where she also serves as a poetry editor for Colorado Review. She lives in Fort Collins, Colorado with her husband and two daughters, and she tends a garden, a flock of chickens, a bearded dragon, a barn cat, a standard poodle, and two goats.

The publisher’s website for her latest collection describes the work this way:

Gatherest defiantly attests to intimacy and our binding humanness amidst an alienating present. In three elegant poems, brushes with contemporary violence are met with meditations on kinship and communication alongside coursing reflections on the elemental foundations that borne and ground our existence. “Daughter,” she addresses, “people are not bad / not evil / people want to be like water / and go where currents send them.” Both candid and hopeful, Steensen stares down modern anxieties, embraces vulnerability and presents empathy as an antidote to pervasive chaos.

In her author statement about Gatherest, Steensen says,

Gatherest is a book of three long poems. While I wrote these poems separately, over time I began to overhear the conversations the poems were having behind my back. They were speaking of the earth, its elements, its inhabitants.

I wrote the first poem, “Waters: A Lenten Poem,” as a serial poem, writing one section per day over the course of the forty days of Lent in 2012. In many ways, this poem is a meditation on Psalm 42:7: “Deep calleth unto deep at the noise of thy waterfalls: All thy waves and thy billows are gone over me.” I was drawn to the image of one depth calling to another depth, and I was excited by the psalmist’s erotic description of water washing over his or her body.

The dailiness of “Waters: A Lenten poem” demanded that I register several events, some national, some personal. The shooting at Chardon High School, the murder of Trayvon Martin, the GOP’s war on women, the death of Adrienne Rich, my then three-year-old daughter’s severe allergy attack, and several birthdays are mentioned here.

The second poem, “I Couldn’t Stop Watching” was written after the first and last section of Gatherest, but it demanded to appear as an interlude, a place to rest between the water that begins the book and the fire that ends it. This prose poem began as an investigation into the sentence and our attempts to manage it via the sentence diagram. I wanted to know what grammar might teach me about how to tread more lightly, how to better parent my children, how to teach and read and write from a place of deeper generosity.

I wondered if the secret wasn’t so much in what I said, but in how I said it. Grammar instructs and excites me. Like “Waters: A Lenten Poem,” “I Couldn’t Stop Watching” ventures into the erotic—Walt Whitman’s blow-job scene, a consideration of the etymology of hymen, how S.W. Clark’s sentence balloons resemble penises. “I Couldn’t Stop Watching” witnesses my body responding to my first lover, the earth. It is almost an elegy. But the earth answers with fire and water, those elements that cancel one another out in their consummation.

The final poem, “Aflame, it Itself made” was written during the month of June 2012 and revised during the month of June 2013. That first June, fires raged all over the country, but Northern Colorado, in particular, was covered in a blanket of smoke. I woke each day to its heavy haze. One day that month, my parents lost their house in the High Park Fire. As a result, shortly after finishing Waters, I found myself writing about fire. As poetry often knows before we do, I shored up what was needed to rest easy in the heat. I gathered it to me.

The publisher’s website shares this sample poem from the collection:

12.

I set my foot down in the hole I dug in darkness so no one would see

I denied you entry

I the laurel treeIf my child is killed by a gun I vow to bring the barrel to the heads of my countrymen

& womenwe do not see how we have been

complete

replete with kindness

with majestyon this day of lent

we went to empire

over our deadwe went

wreathed with grief

& chardon thistleswe went clothed in an anger that does not let itself go easily

we went

to the barnwhere our weapons are

waiting

patientlythere our heart

shall also be