A Conversation with Kelly Weber

By C. E. Janecek

Originally published as a blog post on The Center for Literary Publishing’s website

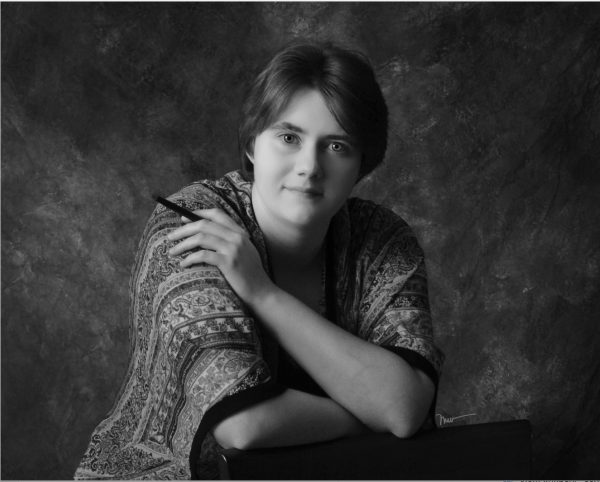

Kelly Weber (she/they) is the author of We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place (forthcoming Tupelo Press, December 2022) and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis, winner of the 2022 Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize (forthcoming October 2023). She is the reviews editor for Seneca Review. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in a Best American Poetry Author Spotlight, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Southeast Review, Salamander, The Journal, Passages North, Foglifter, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Colorado State University and lives with two rescue cats. More of their work can be found on their website.

Kelly Weber (she/they) is the author of We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place (forthcoming Tupelo Press, December 2022) and You Bury the Birds in My Pelvis, winner of the 2022 Omnidawn First/Second Book Prize (forthcoming October 2023). She is the reviews editor for Seneca Review. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in a Best American Poetry Author Spotlight, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Southeast Review, Salamander, The Journal, Passages North, Foglifter, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Colorado State University and lives with two rescue cats. More of their work can be found on their website.

Last week managing editor C. E. Janecek sat down in the CLP’s offices with Kelly to discuss their work, which covers themes such as sexuality, mythology, and lyric verse and literacy.

C. E. Janecek: How would you pitch your upcoming collection, We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place, to readers?

Kelly Weber: This is a collection that grew out of what I felt was a lack of poetic lyric about asexuality[i] and aromanticism[ii]. I realized I just wasn’t seeing different kinds of platonic intimacy and queerplatonic[iii] intimacy in the existing literature. To be really blunt, I’m sex-repulsed, and the more traditional poetic explorations of eros and desire didn’t ring true to me and what I was experiencing. I wanted to find a lyric that could think about that, about the assumptions that readers bring to a poem about love. It really is an attempt to do that and to think about the cishet male gaze and the patriarchy, how all that gets refracted.

For example, there’s this poem I love in the collection, “Epithalamium,” and it’s a kind of queered epithalamium about queerplatonic intimacy. In poems like that I had to think about a reader who may not have an ace or aro framework, how are they going to interpret it? How do you make asexual intimacy legible for an audience who may not get that? In the collection, I put names to it. I’ve got a whole series in there with “ace aro” in the title.

There’s just not yet a literacy for asexuality and aromanticism in poetry. If I’m writing, Gosh, I really love this person, platonically or queerplatonically, how do I convey that in a way that articulates my particular experience? Will the reader be confused, like: I don’t understand why there’s no sex if you feel this way about someone. And as I said, there are so many different perspectives and experiences of asexuality and aromanticism (including and not including sex). I hope this is just one point to add to a much larger constellation of voices and diverse narratives as we go forward.

CEJ: What was one of the first poems you wrote for this collection?

KW: Starting the collection, I center on the myth of Artemis and Actaeon, which I was drawn to, because unlike so many other myths, the one who does the looking is transformed. We’ve usually got a very cishet male gaze on somebody, and they have to transform to escape. This time, it’s the person transgressing who is transformed.

It’s such an ambiguous ending—how do we feel about the fact that Actaeon is torn apart by dogs? It’s so complicated and fraught. Finding the lyricism for this particular aspect of queerness—addressing the male gaze, medical trauma, and pivoting the gaze of classic texts. I was just fascinated by that.

CEJ: What was the process for putting the book together?

KW: The book grew initially out of like, Let’s just try some new experiments. I am ready to take a break from the way I’ve been thinking about poetry. I’ve never thought about the lyric before. Let’s just approach it with a sense of play and experimentation, and the book really developed out of that.

Something I learned from working with my thesis committee was what I call “walling the script,” in which you just put the manuscript up on walls. As Sasha Steensen said, “If it falls down naturally, and if you don’t miss it, let it go.” That was so freeing, so I now have reams of wall-safe tape in my apartment at all times. When I’m working on a book, I just tape it to the wall. I live with it on the wall. As things fall down—or my cats drag them down, or I just feel something doesn’t really fit anymore, and I take it down—it just makes the vision of the manuscript much clearer for me. That was the process of the collection itself moving from the gravity center that’s coming through in this initial set of poems. Over the months it naturally turned into a book as it accelerated to the final point.

CEJ: Since you’re an alum of CSU’s MFA program, I wanted to ask: Which non-workshop class had the most influence on your writing?

KW: There was a great class called “The Ecstasy of Influence” in which Sasha pushed back against Harold Bloom’s idea of the anxiety of influence—of needing to conquer other writers. Instead, we explored how writing and communing with others is really joyful. How are we influenced by other authors? How can that be a really fun and rewarding experience?

We talked a lot about authors who were writing together. Bernadette Mayer and Laynie Brown was one pairing we did together, studying how they’ve influenced each other. In some cases, we studied authors who were writing concurrently, back and forth. I think that’s just so beautiful because it centers relationship instead of competition.

CEJ: That reminds me of my poetry workshops at CSU, when we come together in class and realize we’re picking up on each other’s words and images. We even anticipate each other’s inspiration—finding the same colors and verbs in poems we hadn’t written together and being delighted by the coincidence.

KW: That’s right. It’s group synergy. One of the moments I loved most was when I told my friend a story about this garter snake that had made her nest by my bathroom window. The bathroom window was ground level and rotted so all the snakes came in, and it was just garter snakes tumbling through the window that whole summer—little like green snakes corkscrewing through. I would take them out in an ice cream bucket and toss them into the field.

It was interesting from a poetic perspective. Not very fun from a I need to go to work and I’m tossing buckets of snakes into the grass every morning perspective. Anyway, after I told my classmate that, some weeks later, this beautiful image of snakes coming through a window came up in her poem. And I was just like, that’s so delightful and a useful metaphor for what she was thinking about. Seeing that poem in workshop, I remember putting all these smiley faces around it. It’s like a little love gesture in a way—a kind of little intimacy that I think is really nice.

CEJ: I am fascinated and terrified by the snake story. And I think this segues nicely to the question of work/life balance. How do you approach your writing and time as a chronically ill poet? So many writers give the advice to write every day, to embrace the hustle, to work extra jobs to sustain our art. But I think that’s something disabled poets have to actually unlearn to succeed.

KW: I totally agree. Those are not only productivity imperatives, but they become moral imperatives under capitalism, which always conflates the two. What I found is that I do write every day, but not out of a sense of obligation. I love it and it’s my space of resistance to everything else that is happening in my life, whether that’s illness or disability. That’s great, but it’s also just not the process for a lot of people.

I’m thinking of the author Lidia Yuknavitch—she writes so beautifully about her ebb and flow. She’s got times when she’s writing so rhizomatically—and she’s writing, absorbing, and has this huge output. And there’s times when it goes very still for her—she is in the tide, and it’s time to just listen and be still for a while.

I took most of last year off from my practice, and it was great because my work suddenly felt like a grind. I didn’t want the practice to be that because then it’s not enjoyable. It was hard to learn that I could take time off—but I needed it, and I played a lot of Breath of the Wild. I think that’s important to do, especially if you’re a disabled poet, poet with illness, and in general, breaking away from moral and productivity imperatives. I saw so many people talk about how the pandemic forced them to stop with the hamster wheels that they were on, in ways that they found really productive and refreshing.

CEJ: Your debut collection focuses strongly on themes of chronic illness, reproductive health, medical trauma—especially in the poem “Crown of Screws.” How has this poem, or the book itself, changed for you now that we have a large number of states severely restricting abortion access?

KW: It makes me so angry. One way I use poetry—both reading it and writing it—is as a grief tool. Writing this poem a few years ago, with just my individual experiences, it was a great tool for that. The fact that it’s still a relevant grief tool, not just for me, is frustrating. I feel like it’s always something I’m writing and thinking about because it’s so constant. It’s built into the laws. It’s built into the healthcare. It’s built into these systems that are racist and queerphobic and misogynistic—using language specifically to inflict harm, which is the last thing we would want to do as poets, and yet, the language of the law is so often used to intentionally cause harm.

CEJ: In your collection you’re grappling with what society considers to be the embedded experiences and language of womanhood, while you yourself aren’t a woman. How do you navigate that in your writing?

There’s so many different layers. If I go to the doctor’s office and I’m in pain, and am trying to get the pain taken seriously, that’s just one layer. People want to call it “discomfort,” which is a lot of what that particular poem is about, while I am screaming and they are refusing to call it “pain.” The next layer is often that the language of these medical providers is not inclusive. They offer “women’s services” while there’s such a broader spectrum of people with different gender identities and sexualities that need this care.

CEJ: There’s an enormous irony to the people right now who are insisting on calling it “women’s health” or “feminine hygiene,” when the whole point of the feminist movement before the 2000s was to stop using euphemistic language. And now people are doubling down on this gendered language to reaffirm their perceived “womanhood.”

KW: Yes! And that womanhood doesn’t really exist anyway. If you have a drop-down tab, it’s just going to be like “choice A or choice B,” and they’re not gonna want to put “choice B” anyway. It’s about systems, right? How can we put this in a system? How do you fit into this particular narrative? And sometimes, how do you fit the literal boxes on a literal screen? I think so much of my book is grappling with this—even though I was writing much of this book before I had fully come to terms with my identity—the ways bodies with a uterus are so often shoved into reproductive narratives, gender narratives, and sexuality narratives. If I just go to the doctor and try to explain my sexuality, they don’t even know what that means.

CEJ: They probably approach your sexuality as something to fix, right? Prescribing hormones to increase libido, when libido and sexual attraction are not the same thing.

KW: Exactly. That’s right. There’s enough understanding of different sexualities now that they wouldn’t try to “fix” someone with a different queer identity. But asexuality? Don’t know what that is, sounds like it needs to be fixed. And so you’re writhing in pain in front of somebody, and they don’t acknowledge your pain, they don’t respect your gender identity or your sexuality. It’s like, How am I supposed to get care?

And that’s so much of what this book is about. It’s interesting, because it’s a book about queer “daughtering” in the sense that the speaker is trying to reclaim that in ways that feel right and true. So much of my book is grappling with the question of What is “womanhood”? How is that always a narrative that is applied to the body in these really harmful and reductive ways of who you’re “supposed to” be—these narrative myths of binary gender?

CEJ: Exactly. As we finish, I wanted to take us back to the mythical roots of your writing. I noticed that there are so many different animals in your book—a whole ecosystem to your poetry. How do the speakers and the animals come together in the ecopoetics of your collection?

KW: Certainly. It’s a collection that is aware of living in the Anthropocene. There are poems that are directly about living in a time of incredible climate crisis. It’s thinking about the way the body is a place, and trying to chart that interiority as an ecosystem of possibility.

One of the first poems I’ve written for the collection I took to the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference when it was still very new. It was the first time I was not only trying to articulate a particular queer identity in a lyric poem, but also the first time I was showing it to other people who were not ace or aro. It was so interesting seeing them react to it and to see the ways I was expressing alternately erotic images that are very sensual. So much of this book is about a sensual ecosystem of queer possibility for the speaker—making their experience legible in a landscape of the body and a landscape that holds the body. Thinking about ecosystems that the speaker really loves a lot and the essential qualities of those landscapes that make the speaker’s reality possible—rendering the specific creatures of the speaker, as they respond and react. This particular book is charting interiority and offering a kind of metaphorical alternate reality where the speaker goes, and where we go to hopefully make those alternate intimacies feel possible.

Pre-orders for We Are Changed to Deer at the Broken Place are available now at Tupelo Press. All pre-orders will include a signed broadside featuring the poem “Epithalamium.”

C. E. Janecek is a Czech-American writer, poetry MFA candidate at Colorado State University, and managing editor at Colorado Review. Janecek’s work has appeared in Poetry, Gulf Coast, Cream City Review, Lammergeier, and the Florida Review, among others. Online at www.cewritespoems.com

C. E. Janecek is a Czech-American writer, poetry MFA candidate at Colorado State University, and managing editor at Colorado Review. Janecek’s work has appeared in Poetry, Gulf Coast, Cream City Review, Lammergeier, and the Florida Review, among others. Online at www.cewritespoems.com

Endnotes:

[i] Asexuality is a sexual orientation in which one has little or no sexual attraction to others.

[ii] Aromanticism is a romantic orientation in which one has little or no romantic attraction to others.

[iii] A queerplatonic relationship (QPR) is a relationship categorized by a close emotional bond (greater than friendship) and/or a non-romantic partnership.