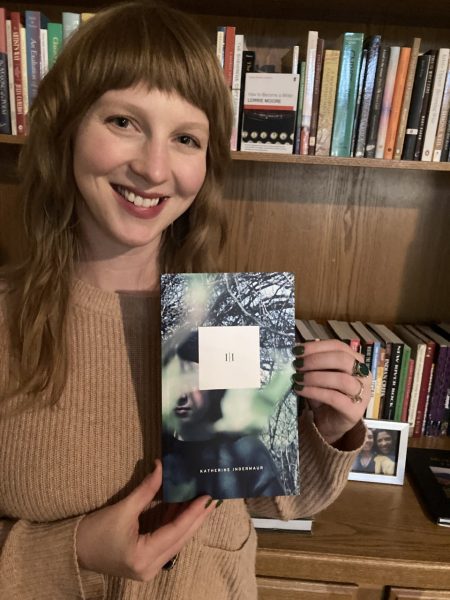

Huge congrats to MFA alumna Katherine Indermaur, whose first book, I|I, will be published by Seneca Review Books on Tuesday, November, 15!

Selected by final judge Kazim Ali as the winner of the 2022 Deborah Tall Lyric Essay Book Prize winner, I|I is a serial lyric essay that explores the mirror’s many dimensions—philosophical, spiritual, scientific, mythological, historical—alongside the author’s own experiences.

Indermaur’s full-length debut has received advance praise from multiple influential writers, including the poet Diana Khoi Nguyen, who offered: “This brilliant lyric flows like a resplendent river replete with tributaries and oxbow lakes, where each bend of water orients the eye to new lines of sight.”

Author Jenny Boully, also noted: “With an eye to both poetry and philosophy, I|I reveals the dangers of seeing, how light and reflection, once unveiled, give way to a broken and distorted existence and perception of so many unending selves.”

Indermaur earned her MFA in Poetry from CSU in 2019 where she was the managing editor for Colorado Review. While at CSU, she was also awarded the 2018 Academy of American Poets Prize.

Now as a first-time published author, Indermaur sat down with CSU English’s Emily Harnden to discuss her writing practice, the craft behind I|I, and more.

A Note on Pronunciation

I|I is pronounced by repeating the personal pronoun “I” once after a brief pause.

Q&A

Q&A

Emily Harnden: How would you describe your upcoming debut, I|I, to readers?

Katherine Indermaur: I|I is a serial lyric essay, so it lives somewhere between poetry and nonfiction. In that way it’s similar to Heather Christle’s The Crying Book, Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, and Paisley Rekdal’s “Nightingale: A Gloss.” In I|I, I explore mirrors and my fraught relationship with them as well as how we see ourselves because and in spite of our reflections.

EH: How did you arrive at placing yourself inside the essay?

KI: When I was writing the first pieces of the book, I was just fascinated by mirrors themselves and did a lot of research on their invention and uses over time. In the back of my mind was always this knowledge that my fascination with mirrors had to do with their being a trigger for my dermatillomania, or skin-picking disorder. I had to be careful placing myself in the essay. In the writing process, doing so was intuitive, but in editing, I had to deeply consider what to reveal—both to myself and to the reader.

EH: I’m kind of obsessed with this idea from Joan Didion: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.” How did your thinking change over the course of writing the book? What surprises and/or challenges did you find along the way?

KI: I totally agree with this! This is why authors publishing their journals petrifies me. My journals are where I figure out what I’m thinking, and often it’s overly dramatized!

Another older meaning of the word “essay” is to try, an attempt. My attempt in I|I is to look at looking. It’s a very fragmented book, and over the course of writing it, it was a challenge figuring out how to make it all cohere, or if there was an arc to it at all. One of the surprises that came out of that attempt toward coherence was the “Practices,” which are a series of instructional pages throughout the book that offer little experiments you can do to look into your own looking, off the page and in your life. I like having these “Practices” as an anchor or a repeated chorus throughout the book. They return us, I hope, to the body.

EH: I’m fascinated by how the book contends with the in-between. The spaces between reflection and distortion, the eye and I, seeing and looking. Can you talk about how the book challenges us to linger within these spaces?

KI: I’m so glad you picked up on this! Lingering in the uncomfortable in-between is something I’ve been obsessed with ever since a yoga teacher of mine told me that the greatest lesson yoga had given her over the years was the ability to sit with paradox. To me, the mirror is paradox. As I write in the book, “Some insist God didn’t design us to see ourselves.” And yet in modern-day science we have this thing we call “the mirror stage,” which is when human babies supposedly reach the developmental stage in which they can recognize themselves in the mirror (rather than thinking it’s another baby). In some state of nature, individual humans never knew what we looked like for our entire lifetimes, and yet there seems to be a stage of our own psychological development in which we have the ability to recognize ourselves.

The book also lingers in the physical in-between—the space across which light travels from source to object to eye. All this space makes the reality of vision feel quite fragile to me, like so much has to go right in order for us to perceive that the balance achieved by perception is, itself, a kind of between-ness.

EH: Let’s talk about the book’s form – how did you arrive at fragments? Did the structure change over the course of writing/editing? How does this structure speak to the idea of multiple selves?

KI: The book was always fragmentary from the start. I studied poetry for my MFA at CSU, so I wrote I|I as a poet would—in small chunks and serially. After I graduated, for a while I spent an hour before work every morning researching mirrors, and those research notes eventually became the basis for much of the book. During my MFA at CSU, my professors had encouraged me to find a cohesive arc for the project that would become I|I. A few years later, the “Practices” became that cohesive thread through the book. However, I still had the desire to preserve that fragmentary feel. Vision, reflection, and the ability to gaze at oneself feel inherently fragmented to me.

There’s an idea from ancient yoga philosophy that I mention in the book that speaks to this fragmented self, the Perceiver: “Mind, from the Sanskrit manas, the perceptive mind, the perceiver, the sense. The Yoga Sutras teach the separation of manas from other qualities of thought and feeling.” In the Yoga Sutras, one of the eight limbs of yoga Patanjali offers is Pratyahara, or the withdrawal of the senses, as a way to achieve enlightenment (another probably more familiar limb to most people is Asana, or physical postures, like what you usually do in a yoga class). This withdrawal, similar to mindfulness, allows for space and time between stimulus and reaction. It’s like the adage “don’t believe everything you think”—inside the mind-self is a deeper self who perceives what the mind sees and thinks. I think of them more as layers than as fragments, though that space between thinking and perceiving can certainly be seen as fragmentary.

EH: What does your writing practice look like post-MFA? What habits from your time in the MFA do you still return to and keep close?

KI: For a while I was writing regularly, especially when I was trying to finish I|I, but now I have a five-month-old baby and things are pretty topsy-turvy. I work full time at CSU as a communications coordinator in the Communication Studies Department, so between work, caring for a baby, and doing all the work that comes with a book launch, I haven’t had much time to write!

My favorite MFA-formed habits that I return to often are reading and taking notes. I find it impossible to write without reading, and so whenever I feel stuck or uninspired, I turn to either my stack of to-be-read books or to a collected poems by a favorite poet. And note-taking takes a lot of the pressure off of the writing process for me. This was something Ada Limón recommended when she came to CSU and gave a reading while I was in the MFA. She doesn’t write every day (which, especially for poets, I feel is crappy advice anyway), and instead amasses a bunch of notes over the course of a month or two before sitting down and writing. I take notes as ideas or phrases come to me in my smartphone, and then occasionally return to them with my journal and handwrite drafts that way. Especially as a new parent, if I don’t type up or write down the note the moment it occurs to me, it’s pretty much gone forever. I can return to the notes as many times as I want and add to or revise them before actually writing a whole poem or essay.

EH: For writers in a similar boat, who feel like there’s never enough time to actually write — what would you share with them?

KI: First, validation: it feels like there’s never enough time because there isn’t! Sometimes you won’t write at all and that’s okay—you’re still a writer. I remember reading that writer Amber Sparks took something like a four-year break from writing after her daughter was born, and she’s since written multiple books. But even if you’re not actively writing or working on a project, I think it’s still important to nurture your creative spirit as much as you can. In The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron talks about taking yourself out on Artist Dates for inspiration. For me, inhabiting the world like a writer is vital no matter what I’m producing, so that looks like approaching things that I already have to do like an artist—decorating my daughter’s room, cooking dinner, reading to her—and trying to do artsy fun things when I can, because writing now, as someone who’s earned an MFA and published a book, has some pressure to it.

EH: Finally: What didn’t I ask that you wished I had? Tell me about it.

KI: If you’re submitting a book manuscript for publication or want to someday soon, I highly recommend reading Jeannine Hall Gailey’s PR For Poets: A Guidebook to Publicity and Marketing and/or Courtney Maum’s Before and After the Book Deal: A Writer’s Guide to Finishing, Publishing, Promoting, and Surviving Your First Book. They’ll both help you feel and act like less of an idiot, which is maybe the best achievement any book can strive for.

Celebrate I|I in-person on Monday, November 14 at 7:00 PM at Wolverine Farm Publick House! In addition to Indermaur reading from her debut, the evening will feature paintings by Elizabeth Fuller, poetry by Robin Walter, and fiction by Claire Boyles.

Preorder the book!

Get your copy from your local independent bookstore, Small Press Distribution, Amazon, or directly from Seneca Review Books for $3 off + free shipping here.

Katherine Indermaur is the author of two chapbooks and an editor for Sugar House Review. She is the winner of the Black Warrior Review 2019 Poetry Contest and the 2018 Academy of American Poets Prize, runner-up in the 92Y’s 2020 Discovery Poetry Contest, and has been nominated for Best of the Net. Her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Alpinist, Coast|noCoast, Ecotone, Frontier Poetry, the Journal, New Delta Review, the Normal School, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Colorado State University and lives within sight of the Rocky Mountains.