~from Katie Haggstrom

“The impulse to dream was slowly beaten out of my by experience. Now it surged up again and I hungered for books, new ways of looking and seeing.” ~Richard Wright

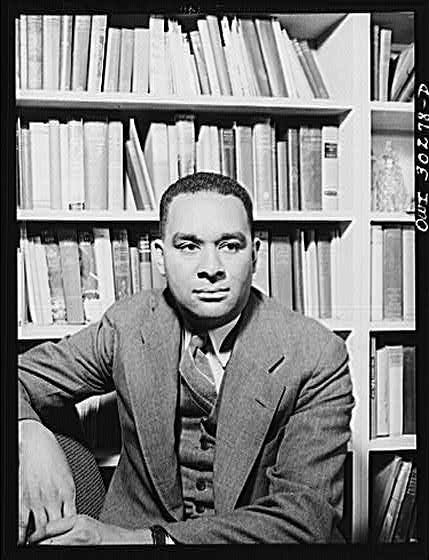

Poet, essayist, and author Richard Wright was born on Rucker’s Plantation in Natchez, Mississippi in 1908. Later, Wright would write his memoir Black Boy (1945) to chronicle his childhood experiences of living in the South and on the plantation. While his parents were free-born after the Civil War, Wright’s grandparents were slaves until they were freed by the war. Wright moved a lot as a smaller child, and as a result, he didn’t attend school regularly until age 13. Even with a late start, Wright excelled in school, and earned the position of class valedictorian of Smith Robertson junior high school.

Wright found the passion, and freedom, of writing at a young age. He was only 15 when he published his first story called “The Voodoo of Hell’s Half-Acre,” which appeared in Southern Register, a local Black newspaper. Unfortunately, there are no existing copies of Wright’s first story.

At the age of 19, Wright got a job as a United States postal clerk in Chicago. The Great Depression pushed him to attend the John Reed Club, a club dominated by Communists. It was through this club that Wright started to make literary connections. These newfound relationships led Wright to publish proletarian poetry for various liberal newspapers, including The New Masses.

Wright’s first novel Lawd Today was originally titled Cesspool. He wrote the book in 1935, although it wasn’t published until after his death. It was through his 1938 collection of short stories Uncle Tom’s Children that he began to really gain national attention for his writing. Some of these short stories drew from the ongoing lynchings in the Deep South, where Wright grew up.

In 1939, Wright applied and received the Guggenheim Fellowship which allowed him to complete his novel Native Son in 1940. It made the bestsellers list and was the first book by an African-American writer to be picked for the Book-of-the-Month Club. This book was later adapted into a play and in 1941, Wright was awarded the Spingarn Medal of the NAACP for “noteworthy achievement.” He even went on to start at the main character in an Argentinian version of the film.

In April 2009, Wright was featured on a U.S. postage stamp. In 2010, he was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Many of his books continue to be required reading in American high schools, universities and colleges.

Wright was often criticized for his depictions of violence in his books. Today these texts serve as a reminder of the racial inequality both Wright and other members of the black community experience in America.