~from Communications Coordinator Jill Salahub

I spent yesterday brainstorming a list of women to feature on the blog this month. It’s Women’s History Month, and we’re celebrating specifically women who’ve made contributions to literature and education. Because there are so many, I toyed yesterday with limiting my list to U.S. citizens — and yet, that means leaving out women like Margaret Atwood and Virginia Woolf and Alice Munro. This morning, I was still unsure what we should do, and undecided about who we’d feature first.

And then, as it does when you allow yourself to be open and curious and patient, the answer came to me. I was on Twitter (which is part of my job), and noticed that it’s World Book Day, (at least in the UK and Ireland). As I scrolled through #WorldBookDay tweets, looking for things to share on the English department’s Twitter account, I saw a post that made it clear who my first Woman’s History Month feature would be. She’s not American, and not yet a woman, and the book she wrote wasn’t something she ever intended to be read by other people, but it has always been one of my favorites so please indulge me this diversion, kind and gentle reader.

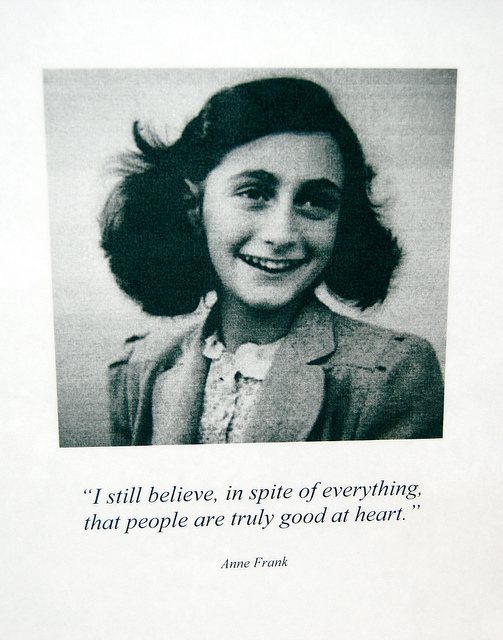

As a fourth grader, I read Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl for the first time. When she made her first entry in her diary, Anne was four years older than when I first read it, but there was something about Anne’s voice that seemed to come from inside my own head. She was so much like me. She loved books and movies, had one older sibling, wanted to grow up and marry and have children and to be an actress or a writer, she was independent and stubborn but also sensitive, she felt like no one who knew her really knew her, that no one saw her true self. She wrote in her diary because “I want to write, but more than that, I want to bring out all kinds of things that lie buried deep in my heart.”

I identified with Anne’s isolation and her hope for the future. And even at that young age, it was becoming clear to me that for every person like Anne, full of hope and possibility, there was another full of pain and anger. And at times, all four qualities could crowd inside a single person. We all suffer, and intentionally or not, we cause others to suffer as well — a hard truth I was learning early on.

Anne Frank was born in Germany, but her family was Jewish. With the rise of Hitler, when Anne was only four and a half, her family fled Germany for Amsterdam, where her father started a business — becoming a wholesaler of herbs, pickling salts, and mixed spices used in the production of sausages. When the threat of war in Europe grew, the family made failed attempts to emigrate to England and the U.S.

With the outbreak of World War II, and the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands, the Franks tried one more time to emigrate to the U.S., but failed because the government was concerned that people with close relatives still in Germany could be blackmailed into becoming Nazi spies. Things worsened in Amsterdam, with Anne and her older sister moved to a Jews only school and her father taking action to prevent his business from being confiscated as Jewish-owned, transferring his shares and resigning as director. When Anne’s older sister received a notice to report to a German work camp, the family made the decision to go into hiding. They moved, along with another family, into a secret annex in the rear of the building where her father had worked, in a series of rooms whose entrance was concealed by a bookcase.

After two years, they were discovered and deported to concentration camps. Anne and her sister were transferred to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp from Auschwitz, where they died (probably of typhus) a few months later. Anne was only 15 years old.

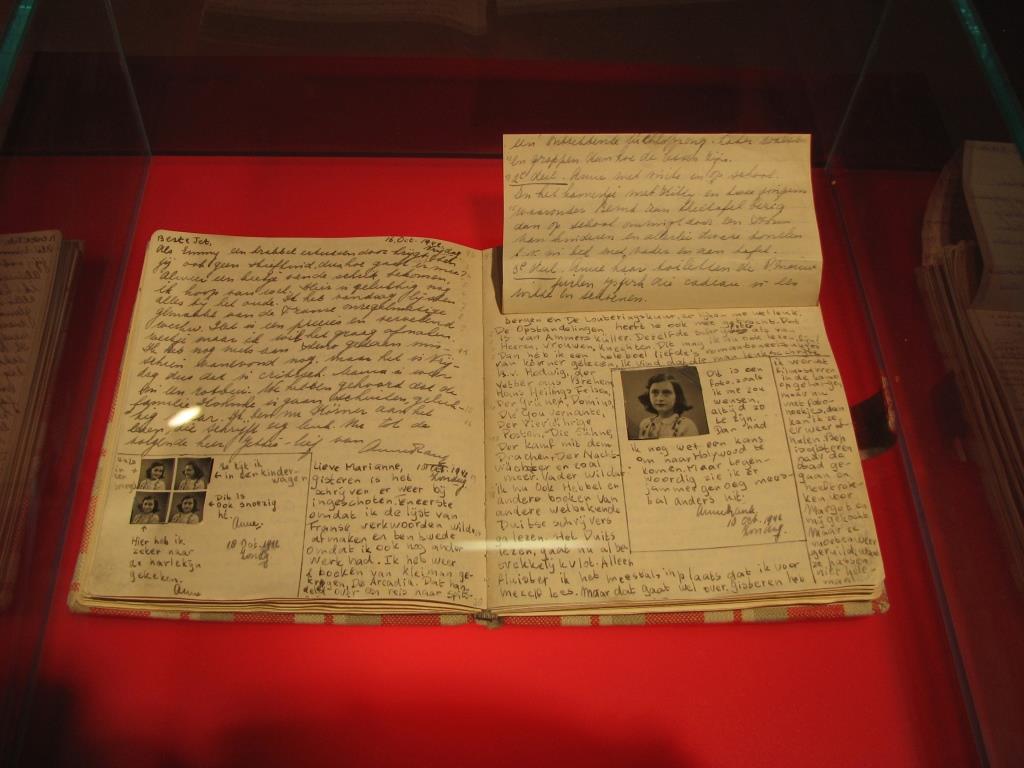

Anne’s father was the only one of those who hid in the annex to survive. He returned to Amsterdam after the war to find that Anne’s diary had been saved by one of the people who had helped them hide for those two years. Anne had received the diary as a present on her 13th birthday, and in it had documented the two years they’d been in hiding. She wrote regularly in it, until her last entry on August 1, 1944, (three days later, the German police arrived at the annex and arrested the family). Her father’s efforts led to the diary’s publication in 1947. It was later translated from Dutch and published in English in 1952 as The Diary of a Young Girl.

It has since been translated into over 60 languages, and been the basis of many plays and films. Eleanor Roosevelt said it was “one of the wisest and most moving commentaries on war and its impact on human beings that I have ever read,” and John F. Kennedy said, “Of all the multitudes who throughout history have spoken for human dignity in times of great suffering and loss, no voice is more compelling than that of Anne Frank.” In 1999, Time included Anne Frank on their list The Most Important People of the Century, stating: “With a diary kept in a secret attic, she braved the Nazis and lent a searing voice to the fight for human dignity.”

I’ve read this book many times over the years. Every time, I brace myself for the disappointment that I think will come because I never believe that the actual book can possibly match my precious remembered experience of it. I expect that it won’t be nearly as moving or meaningful—but it is, every time. And every time, my heart breaks again—that we as humans can be both so wonderful and so horrible.