~by English Department Communications Coordinator Jill Salahub

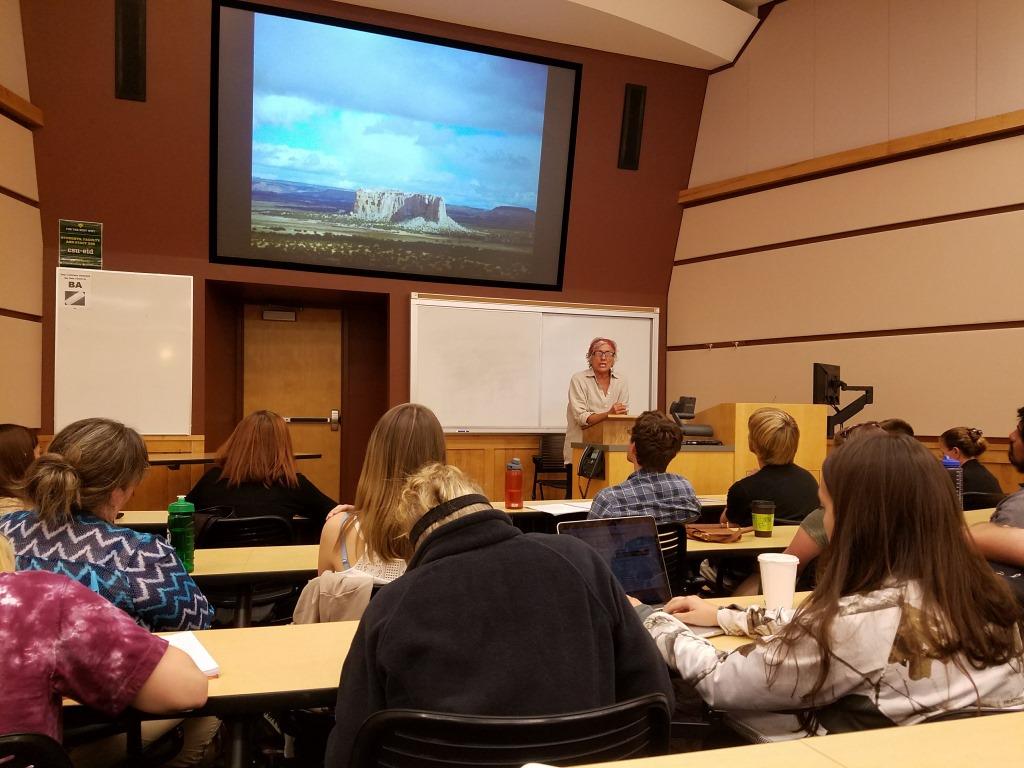

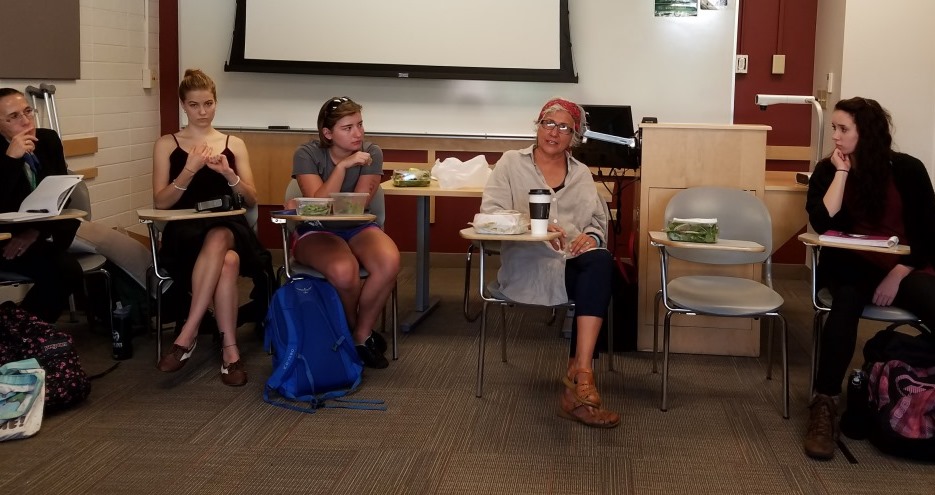

Phi Beta Kappa along with the English department welcomed poet and sculptor Nora Naranjo Morse to CSU for a two day series of events – class presentations and discussions with students, as well as a public lecture. She will travel to ten campuses altogether to do the same as part of the Phi Betta Kappa Visiting Scholar Program, whose purpose is to “contribute to the intellectual life of the campus by making possible an exchange of ideas between the Visiting Scholars and the resident faculty and students.”

I spent the weeks leading up to her visit helping to advertise the event and in the process getting to know her work a bit better. I couldn’t wait to meet her, hear her talk about her life as an artist. I was lucky enough to shadow her during her visit, using my position as communications coordinator to justify attending her class visits as well, (just one of the perks of my job). The third time I showed up at one of her sessions, she laughed and said, “oh, it’s you again!” and wondered if I was a student as well as working for the department.

Nora Naranjo Morse is a member of the Tewa tribe from Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico where she lives and works, a potter and poet, an artist who engages both her hands and her heart in her art. Her mother and her mother’s mother also worked with clay. During a class visit at CSU, she told students how when she was sent to public school, she wasn’t a very good student, couldn’t understand what was being taught. She took refuge in pen and pencil, and her anchor during class was doodling. She would go home and see her mother making pottery, see the meditative state she was in, as if the work took her to another place, and she’d think to herself, “I want that.”

Naranjo Morse is the “youngest daughter of Rose Naranjo, a well-known Santa Clara-Laguna potter, has eight siblings, all of whom have made pottery at one time or another in their lives” and “After Taos High School and the College of Santa Fe, taking ten years to get her bachelor’s degree, Nora traveled and wrote poetry. Then she married, had two children – girl and boy twins, who she says have changed her life – and built her own house,” (https://www.cla.purdue.edu/WAAW/Peterson/Naranjo.html).

Her bio on the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar Program page describes her work this way: “Her installation exhibits and large-scale public art speak to environmental, cultural, and social practice issues.” Her sculptures and films are in collections at the Smithsonian Institution, the Heard Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Albuquerque Museum, and the National Museum of the American Indian.

Although she is known for her work with clay, that material does not limit her creativity or curiosity. Nora Naranjo Morse‘s work continually evolves, engaging directly with issues of both contrast and connection, true to her lineage even as her work continues to transform. She works not only with clay, but with words, metal, video, and even trash. Two of Naranjo Morse’s larger projects are Numbe Whageh at the Albuquerque Museum in New Mexico and Always Becoming at The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, projects where the process and finished pieces worked with instead of against the environment, telling a story of how the environment is a living place and her people’s connection to it a living and thus evolving thing.

Numbe Whageh is a part of the Cuerto Centenario project in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and was Albuquerque’s first “land art” piece. Numbe Whageh is a phrase from the Tewa Pueblo language and means “the center place.” Naranjo Morse also described it as “your place where you breathe, your place where you know who you are, your community.” Naranjo Morse says about the project, “This controversial project focuses on the historical treatment of Pueblo people by Spanish conquistador Don Juan de Oñate during the late 1500s. Among other subjects, this project looks at issues of monuments, who makes them and why.”

It was fascinating to hear Naranjo Morse talk about the project. In 1996, a group asked that a bust of Juan de Oñate be installed in the downtown area of Albuquerque to commemorate the anniversary of his arrival in New Mexico. There was, understandably, resistance from the native people in the community. Three artists were invited to work on the project, including Nora Naranjo Morse. Initially, they worked together to come up with a piece that would work for all the peoples involved. Naranjo Morse was torn about being involved because of all it meant, the controversy, but ultimately wanted to do something meaningful.

At some point during the TEN year process of this project, years fraught with complication and tension, when it became clear that there would be no agreement about how to proceed, Naranjo Morse began work on her own piece, a land-based landscape project next to where the busts where placed. The contrast between the two installments highlights the differences in how the various people involved see history, how they see their place in history. Visitors to the site are met with the visual contradiction of the two pieces, which is reflective of the conflict between the people. “I made this piece for native people … but really it’s for everybody to remind us of where we come from, where we are going, what we leave behind.”

Naranjo Morse showed pictures of the finished Numbe Whageh and talked about how it’s drawing wildlife to that area, situated right in downtown, and that even a coyote has been seen there. In a video she produced about the project, she says,

I think that extraordinary sense of place has helped native people to create a very strong sense of self in relationship to the physical world because that was the balance they strove for in their spirituality. They understood that simplicity and strength of that land molded our work sensibility and kept us alive as a people.

In much of her work, Naranjo Morse draws inspiration from the unique relationship that her people have to the environment, and her piece Always Becoming is no different. The piece includes a series of sculptures made from earth, clay, and wood, and is intended to “melt back into the earth over time.” Naranjo Morse says of the project,

We created sculptures that represented culture, environment and home. The ephemeral nature of Always Becoming opened unexpected doors, revealing symbols of cultural and environmental transition through the process of dissolving. A living art piece demands stewardship and to this end, new opportunities emerge for the next generation of people exploring issues of cultural and environmental transition.

Talking with a group of CSU students about her creative process, Naranjo Morse said that it is “alive and continuous” and “is so open and forgiving, gives me confidence and curiosity,” even as it “takes a lot of work and it’s every day.” She doesn’t just make art, finished pieces, but she lets it transform her in the process.

While at CSU, she explained to students how her work has been evolving, specifically in terms of the materials she uses. On the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar Program website (https://www.pbk.org/WEB/pbkdocs/Visiting_Scholar/Lectures/Naranjo%20Morse%20Phi%20Beta%20Kappa%20Lecture%20topics.pdf), she says,

A couple of years ago, I went to gather clay at the same clay vein our pueblo has been using for generations. Once the clay was gathered, I walked to the top of the hill. From the hilltop you could the Santa Clara pueblo dump below. The close proximity of the pueblo dump to the clay vein was startling. Plastic toys, couches, stoves, etc. covered the land and seemed to be traveling at a slow but steady pace toward the clay pit. It was disturbing and yet curiously compelling. The visual juxtaposition of clay and trash perfectly illustrated the enormous cultural and environmental shifts that contemporary Pueblo people face.

In one of her class visits, she talked about this experience, of finding the trash, taking some back to her studio and transforming it. “What do you do when your sense of self and place are so intertwined but the place changes so drastically?” The answer for Naranjo Morse, at least in part, is you make art, immerse yourself in the creative process and try to figure it out, “creating expression from where your truth is at.”

At dinner at the end of a long day of class visits and presentations, I asked Nora about the travel and effort involved in the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar “tour.” She said it was true, that she barely had time to unpack before she had to head out for another visit, but she has a real sense of purpose. This work will allow her to build another structure on her land where she already has her home and her studio. Her dream is to have a place where visiting artists can come and stay.

The Tewa homes in New Mexico are adobe, constructed using dirt, straw, sand, and wood covered in clay. The clay they use is micaceous, so when the sun hits it, they glow as if they are made of gold. During her visit to CSU, Naranjo Morse talked about how when she works with the clay, her skin gets covered in the glittering dust. There’s a particular magic of her lineage, a medicine born of the material she uses mixed with her own effort, a light that glows from her work embedded in a history and heart particular to a place and a people. Nora Naranjo Morse’s willingness to share that magic, that medicine with us through her work, her time, her effort, and her travels is such a precious gift. We are so grateful to her for coming to CSU.