by English Department Communications Intern Kara Nosal

“You know how it feels when prose goes, not through your head, but through some other organ, like your skin?” Peter Heller asked us, the audience at his February 5th reading at the University Center for the Arts (UCA). I recognized many familiar faces from the English department, students and professors alike sitting in the rows. We nodded. We were writers, too. He told us that he’d like to talk about craft and process tonight. I readied my pen to take notes about the ins and outs of character development, about leitmotif, about point of view. Maybe I had been in a classroom too long. Heller’s craft advice, like unseen rapids in a river, would jolt me awake.

At age eleven, Heller read Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time and it was then that he knew what he wanted to do for the rest of his life. I’ll give you one guess, but first, here’s a hint: it wasn’t writing.

Primarily, Heller wanted to have adventures. Hemingway wrote short stories about bullfighting and war. Heller, too, wanted to experience of life to the point that he had to grit his teeth and hold on. His love of writing would serve two purposes: it would be Heller’s way of recording his excursions as well as his means to get him there.

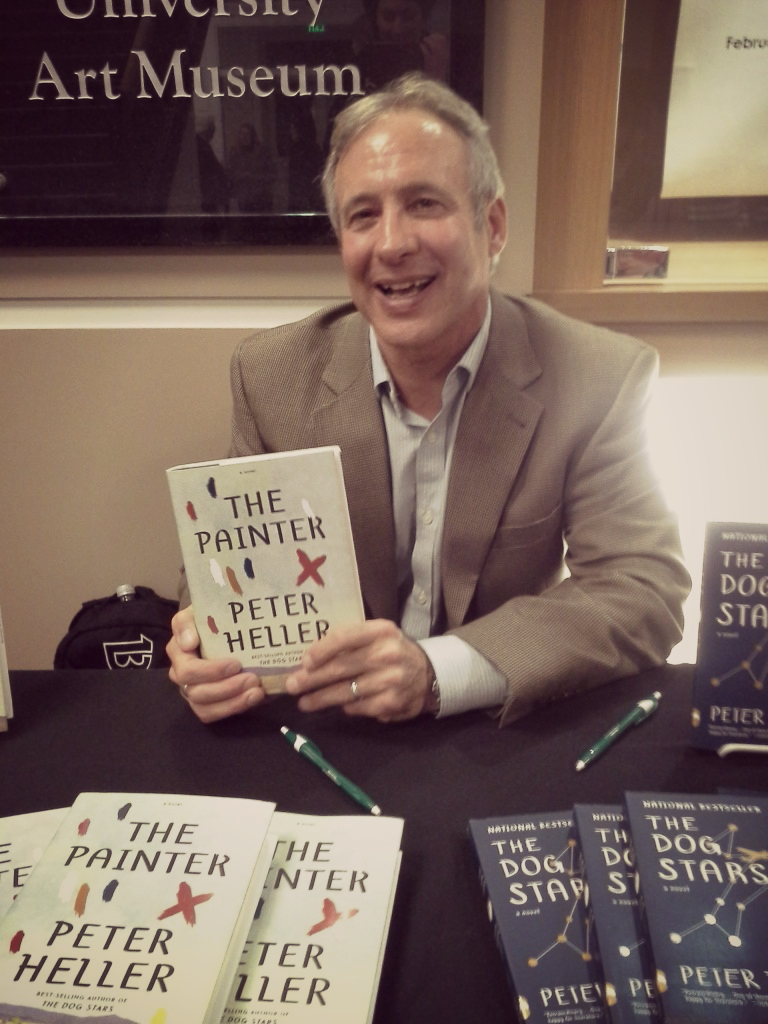

Heller’s most well-known book is also his debut novel, The Dog Stars. It’s a post-apocalyptic novel that follows the life of a survivor named Hig. His newest book, The Painter is about an edgy expressionist painter in Taos, New Mexico who mourns a family tragedy through violence and art. But before he was a novelist, Heller started as a contributor to various magazines, making his name as an author by primarily becoming an adventurer.

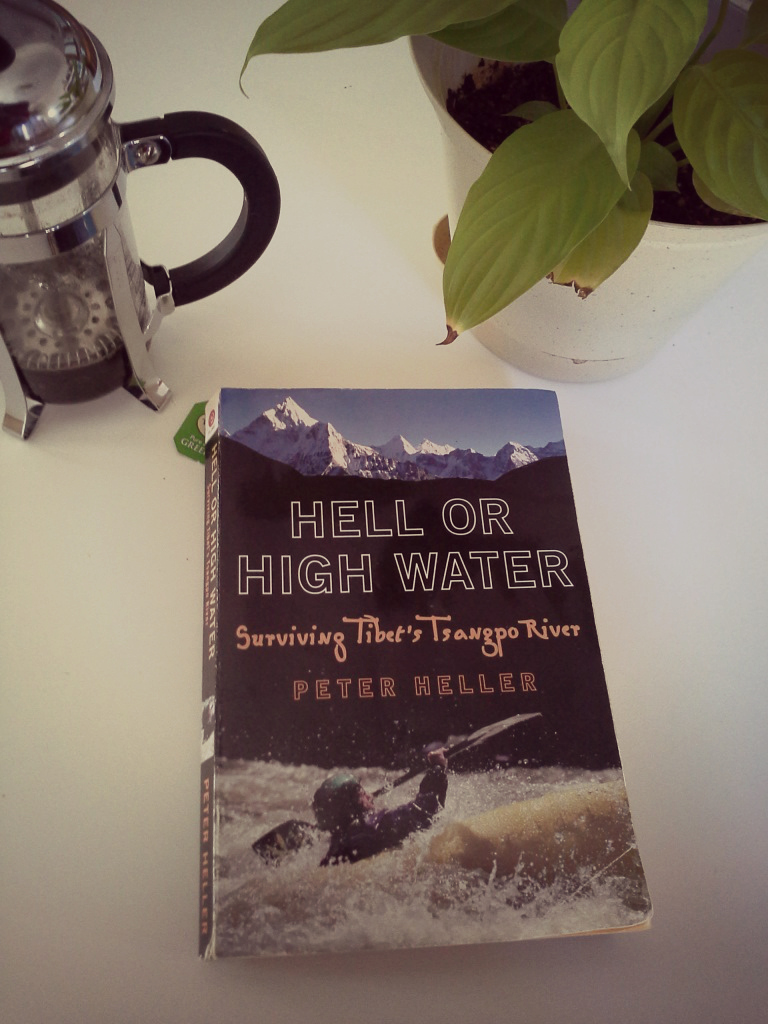

On assignment for Outside, Heller wrote Hell or High Water: Surviving Tibet’s Tsangpo River, which records the voyage of a team of kayakers determined to ride an impossible river. National Geographic Adventure set him aboard an eco-pirate ship chasing after a fleet of Japanese poachers in The Whale Warriors: The Battle at the Bottom of the World to Save the Planet’s Largest Mammals. Men’s Journal printed a piece which recounted paddling into an inlet used to slaughter dolphins as part of the filming crew for The Cove, the Academy-Award-winning documentary. Most recently, Heller took up surfing in order to write Kook: What Surfing Taught Me about Love, Life, and Catching the Perfect Wave.

Nonfiction, for Heller, has never been an excuse for dull writing. “I wrote with as much poetry as I could,” Heller told us. He described how he writes into the music of language, hoping to find the subject at the other end. Stephen King does this too, as Heller pointed out, defending his technique. He joked that the Literary FBI might come after the two of them for writing wrong. To approach nonfiction in this way is to acknowledge and revere some guiding force, a current that pulls the writer along. Some might call it a muse. Heller spoke of hearing voices.

The Dog Stars, he explained, wasn’t fully under his control. The first lines came to him and he merely wrote down what he heard, “I keep the Beast running, I keep the 100 low led on tap, I foresee attacks.” The voice introduced itself to him and its name was Hig, “Big Hig if you need another.” Heller began scribing as the voice told its story to him in a coffee shop. Heartbreaking moments in Hig’s tale caused Heller to cry, but he kept writing, despite the wary eyes of other customers clutching their cappuccinos. “Don’t think. Just listen,” became his mantra. When Heller realized what was on the page was of the post-apocalyptic genre, he was resistant. It was not what he had planned on writing, but trusting the wisdom in the voice, he kept recording. Writing fiction, it seemed to me, required the same creative process for Heller as when he wrote nonfiction. The experience — whether it be of cool water and physical pain or of musicality and mystery — comes first. The art is only a product of it.

When Heller read passages from The Painter, I was absorbed in the character’s voice. He introduced us to Jim by reading, “I used to get drunk before interviews like this, but this was eight a.m. a little too early for even me. The interviews tended to make me feel like a rabbit or a lamb caught above tree-line at nightfall” (page 170 in the book). Instead of taking bullet-point notes about diction, I began journaling out of inspiration. It struck me that Jim, the narrator, is not an accumulation of words on the page. I had come to know him in a few pages and I felt as if I were meeting Jim face-to-face. Heller’s goes beyond detailing Jim’s physical description and mannerisms and somehow captures the sense of this person. Maybe this kind of character sketch is only possible by practicing deep, obedient listening, as Heller suggested. Jim’s philosophy on painting echoed what I had been hearing from Heller all night. Jim paints like Heller writes: “simply and to feel a cooling, the calmness of craft, of being a journeyman who focuses on the simple task: pin this one corner together and make it fit in an expanding universe” (page 147).