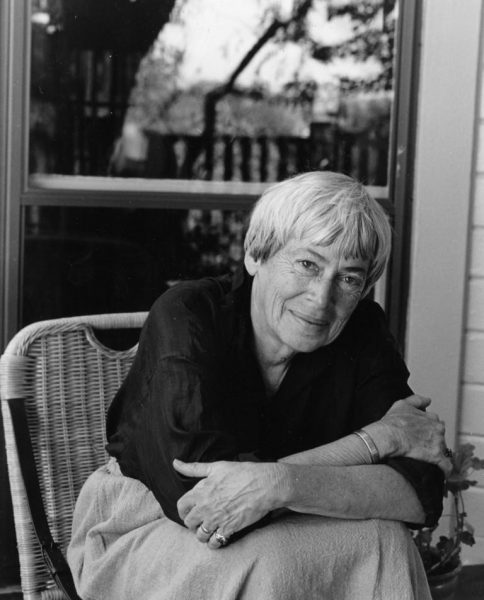

Novelist and short fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin died on January 22nd at her home in Portland, Oregon, at the age of 88. She was born in 1929 in Berkeley, California, daughter of an anthropologist and a writer. She wrote her first fantasy story at age 9, and submitted her first science fiction story for publication in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction at age 11 — sadly, it was rejected. From 1951 to 1961 she wrote five novels, which publishers also rejected, considering them “inaccessible.” In the 1960s, she began to finally publish some of her short stories, and then novels. Despite this seemingly difficult beginning, she went on to be a widely acclaimed and awarded author who was known, loved, and respected by many.

Le Guin worked mainly in the genres of fantasy and science fiction, but also authored children’s books, short stories, poetry, and essays. As of 2015, she had published twenty-one novels, eleven volumes of short stories, four collections of essays, twelve books for children, six volumes of poetry and four of translation, and had received many honors and awards including the Hugo, Nebula, National Book Award, PEN-Malamud, and the National Book Foundation Medal. In 2016, The New York Times described her as “America’s greatest living science fiction writer.” Her New York Times obituary called her “the immensely popular author who brought literary depth and a tough-minded feminist sensibility to science fiction and fantasy with books like The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea series.”

Le Guin has had a lasting effect on many right here in the English department. We asked them to share a few paragraphs about a particular text that had an impact on them, a teaching memory, a favorite quote or story or book, why she was an important figure, etc., and here’s what they had to say.

From Airica Parker: Many people don’t realize that Ursula K. Le Guin was a student of the Tao. As one of the essential texts of Taoism, Tao Te Ching has been widely translated, and Le Guin’s A Book about The Way and the Power of The Way is one of the most gracefully poetic translations that I know of in English. As a reader of her translation, I felt that she allowed herself to embody the ancient text on her own terms. Of her efforts with the 81 verses, it is her poem for Verse 7 that I most cherish:

Dim Brightness

Heaven will last.

Earth will endure.

How can they last long?

They don’t exist for themselves

and so can go on and on.

So wise souls

leaving self behind

move forward,

and setting self aside

stay centered.

Why let the self go?

To keep what the soul needs.

From Kelly Webber: A fiction writing teacher introduced me to LeGuin’s Earthsea series during my freshman year of college. I was taken by her ability to write from both a YA and adult perspective, one of the reasons the teacher had recommended it. I devoured the trilogy and have gone back to the books at various times over the years. When I read Left Hand of Darkness, I was in the first year of my MSE, and I led the discussion over it for Rekindle the Classics in yet another “first” year, the first year of my MFA at CSU. It feels like LeGuin has been there with me over each threshold of my adult life, herself a person of many firsts: one of the first women to break into sci-fi, one of the first authors to write a YA fantasy book, one of the first people (that I read, at least) to articulate just how much world literature that realism, in all its recency, has marginalized. LeGuin will always be important to me as a writer who has taken us across, and back to, those doorways in literature and in life.

From Todd Mitchell: In sixth grade, I remember reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Our class had a heated discussion of this story (and whether one would stay in Omelas or leave it, knowing that this utopia is paid for with the suffering of others). When the bell rang, this discussion spilled out of the classroom and into the lunchroom, then onto the playground after school. It was one of the first times I’d experienced a literary discussion of this magnitude, and I was hooked. It was only later that I realized our society shared many similarities with Omelas (including luxuries built on the suffering of children) and my understanding of the world, and of literature, deepened further. In many ways, my fascination with discussing literature began with Le Guin’s work as she showed me how powerful stories could be in changing the way we understand the world.

A few years later, I read the Wizard of Earthsea, and my understanding of what stories could do was once again broadened. Le Guin tore down genre barriers, and showed that something could be at once fantasy, science fiction, and literary. In doing so, she opened doors that many other writers (myself included) have since passed through—combining genres while writing fiction that engages current social issues. As Le Guin said in a speech in 2014, “Resistance and change often begin in art and very often in our art, the art of words.”

For me, and for a great many other writers I know, she’s been an inspiration for decades. Her presence on this earth will be well-missed, but her influence will continue to be felt.

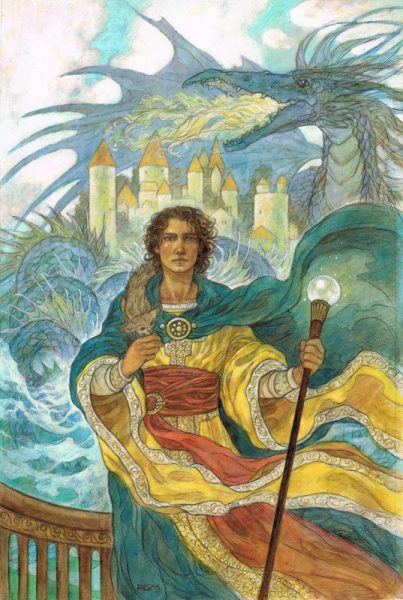

PS: Recently I learned that my cousin’s career as an artist was also deeply impacted by Le Guin, as one of her first paid commissions was to create the covers for Le Guin’s Earthsea books. I’ve included a couple of these images (by Rebecca Guay).

From Terri Sandelin: I fell in love with her writing forty (forty!) years ago. A Wizard of Earthsea. The Left Hand of Darkness. The Dispossessed. The Word for World is Forest. And then all her wonderful essays. When I read about her death the other day, I glanced over at my desk and saw the copy of Words Are My Matter that I had just recently picked up. I’ve spend the last day pulling some of her books off the shelf, reading passages here and there, remembering how I felt first reading them. So, here’s a bit from The Farthest Shore.

Ged has finished his last great deed and burned out the last of his magic in doing so. The dragon Kalessin lifts him up and flies away with him.

The Doorkeeper, smiling, said, “He has done with doing. He goes home.”

And they watched the dragon fly between the sunlight and the sea till it was out of sight.

From Sarah Sloane: Ursula K. Le Guin in My Cabin.

I’ve loved Ursula Le Guin’s books since I stumbled on The Left Hand of Darkness in high school between doses of Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov and all the other sci fi writers whose books lay around on my father’s bookshelves. Why wouldn’t I fall in love with her softer sci fi after being raised on the fare of A.E van Vogt’s endless tale––putting the saga back in saga––of the oppressive Empire of Isher and its mysterious weapons shops? In college I had a dream of a people called “the dispossessed,” and when one month later I found a novel of the same title in a used bookstore near Middlebury College, I felt Ursula Le Guin and I were meant to be.

I’ve kept on reading Ursula Le Guin’s oeuvre for the last 40 years, both her nonfiction and fiction, the latter for her gender-bending characters, but the former for her humor as well as her feminism. Think, for example, of Le Guin’s response to those evangelical Christians and scientists who said it was impossible to simultaneously believe in God and science. Le Guin: “[They say] if you believe in God you can’t believe in evolution. But that’s like saying if you believe in Tuesday you can’t believe in artichokes.”

In graduate school I gave a paper at CCCC with David Bleich and Ursula Le Guin’s daughter, Caroline, a doctoral student in English at Indiana. I am mourning all the stories that Ursula Le Guin didn’t get to write, which is certainly a reader’s selfish grief, and does not hold a candle to the sadness of a daughter losing her mother.

Around 1995 I heard UrsulaLe Guin read some of her new work at Elliott Bay Books in Seattle. It struck me then how content she was with what she had written: not smugness but just joy in the made. She laughed at her own jokes. She smiled often. Whether hers was a hard won contentment, her palpable pleasure in what she had written warmed my cockles.

About ten years later, in September in 2005, I was lucky enough to have been granted a writers’ residency at Hedgebrook on Whidbey Island in Washington State. Each of us writers was given her own cabin in the pine-soft woods for a month. In the early morning a mist still curled around the trees. At night it was beyond dark, the kind of dark where if you lost your flashlight you were truly sunk. One night around midnight I lay alone in a large field and listened to two horned owls’ round hoots burrow through the mist and open up above me. It was the same field where I startled a coyote one morning. I was sitting cross-legged and utterly still as I saw it trot by not ten feet away. I think it must have seen my eyelid blink because it froze and looked at me, then rapidly ran away.

Mine was Owl Cabin and had a wood-burning stove, two giant glass windows where I could stare at the trees, a small kitchen, and a bed in the loft. You entered the cabin through a Dutch door perfectly rounded at the top like a hobbit hole.

In this cabin there was a journal that writer-residents over the years had added to. One morning, the top of my Dutch door open to catch some rare sunshine among the cedars and pines, I was flipping through the notebook in Owl Cabin and idly reading other resident authors’ sweeping narratives and serious meditations on the meanings of reading, writing, and life. I remember a long entry about a party where several of the residents ended up in a hot tub—which was odd because Hedgebrook didn’t have a hot tub.

As I was flipping through the notebook I saw a drawing and stopped. It was an outline of a lizard, I thought, or maybe some moister wood creature. It took a minute before I realized it must be a salamander, although now I know through looking up salamanders in that area, that it was probably an Ensatina salamander. Next to the amphibian’s outline was a short, simple entry about finding this salamander just outside my cabin’s Dutch door, a sticky pink amphibian sunning himself on the stone stoop. All the detail of that creature—his size, the shape and direction of his body, the quality of his tail—were painstakingly described by the writer/artist who turned out to be, yes, Ursula Le Guin. For it turned out that a year or two before, Ursula Le Guin had lived and written inside my same cabin. Her drawing and spare words in the journal were what she had left behind.

In the middle of entries marked by self-preoccupation or discursive sections on hot tub plumbing, Ursula Le Guin found what to write about in a creature a few inches big living just outside her door. “Pay attention,” Le Guin’s drawing of a salamander said to me. Ignore the parties and the plumbing pay attention to what small things live right in front of you.

Several years after that, one of my creative nonfiction workshops smelled of fear, and that anxiety revealed itself unfocused prose, blurry characters drowning in a generic sea. I told my creative nonfiction students to think less about the world in general, this mush of ocean and earth, sleepy blue oceans interrupted by bits of green and beige where people live. I suggested they write about a person they knew really well or wanted to get to know. I suggested they describe the world they can find no farther away than where their own arms could reach, at least for a little while.

I told them the story of living for a few weeks in a cabin Ursula Le Guin once wrote in too. I told them what Le Guin wrote and drew in our cabin’s journal, and I told them that they needed to be like Le Guin in that they need to find their own topic, the one that matters, the salamander. “Find the Salamander!” became a frequent reprise in our workshop, and by the end of the semester they were threatening to make tee-shirts with that slogan. I may get one made too, in homage to Ursula Le Guin, already sorely missed.

“What if you’ve already read all of her books? Where do you go from there? Well, one place to start is the long list of books she’s recommended. (She always balked at naming her ‘favorite’ books.) Here are more than 75 of them: books she mentioned in interviews, or wrote about on her blog, or gave to the Strand for her ‘authors bookshelf,’ or books she blurbed.” 75+ Books Ursula K. Le Guin Recommended